Reverse amnesia: How a tennis match revived a forgotten past

Memory, which links us to our past and shapes our sense of identity, is the thread that allows us to recognize ourselves over time. But what happens when this thread breaks, when memories fade, and the past becomes inaccessible? Retrograde amnesia is a world where landmarks disappear, leaving individuals adrift in a present without roots. This reality, though unsettling, is the experience of those who suffer from this form of memory loss, suspended in a time that no longer belongs to them.

Far from being a simple memory disorder, retrograde amnesia is a captivating mystery within neuroscience. While its causes can vary, ranging from head trauma and intense stress to brain lesions, its manifestations often challenge our understanding of how memory works. What makes this phenomenon even more intriguing is that it is not always permanent. In some cases, memories that once seemed lost can suddenly and spectacularly resurface, triggered by a detail, a place, or a sensation. This ability of memories to return unexpectedly adds a layer of complexity to our understanding of how memory retrieval operates and highlights the resilience of the brain in the face of cognitive disruption.

When the past fades

On April 12, 1992, M.M., a 24-year-old man, experienced a life-altering event. After losing control of his car and crashing into an obstacle, he emerged with only a small cut on his lip that required a few stitches. At the time, nothing suggested the profound changes that would soon unfold. Three hours later, an odd sensation overtook him. His memory seemed to vanish, like words erased from a blank sheet of paper. He no longer remembered. Not the accident. Not what had happened before. The fragments of his past scattered, elusive.

Unlike some memory disorders, M.M. retained his ability to learn and retain new information. However, his past appeared to have been brutally stolen from him.

His oldest memories, such as those from childhood, remained somewhat preserved, fragile but present, like relics spared from oblivion. However, recent events slipped away from him as though they had never occurred. His recent past had become an unknown land, an invisible page he could no longer read.

As the days passed, M.M. showed signs of partial recovery. Occasionally, a detail or an object would trigger isolated flashes of memory. However, these flashes remained fragmented, unable to form a coherent picture of his past. His experience serves as a haunting reminder of how memory, the very fabric of our identity, can be disrupted, leaving us adrift in time, unable to fully reclaim the self we once knew.

Memory’s hidden levers: How a simple game unlocked forgotten worlds

A month after the accident, an otherwise insignificant event changed everything for M.M. During a tennis match, he suddenly realized that he was repeating a technical mistake he had made years ago. This detail, embedded in his procedural memory, acted like a lever.

Within minutes, his memories began to flood back, starting with those related to tennis, followed by a cascade of autobiographical events. “It was like turning on a tap, and the water began to flow,” he would later explain.

This case highlights a rare but fascinating phenomenon: the spontaneous recovery of memories triggered by specific contextual cues. M.M.’s experience raises important questions about the underlying mechanisms of memory and how emotion, context, and neural networks interact. M.M.’s case is not merely spectacular; it offers a unique glimpse into the intricacies of human memory. To better understand what happened in his brain, let’s delve into the possible mechanisms behind retrograde amnesia and the conditions that allow memories to resurface after periods of apparent loss.

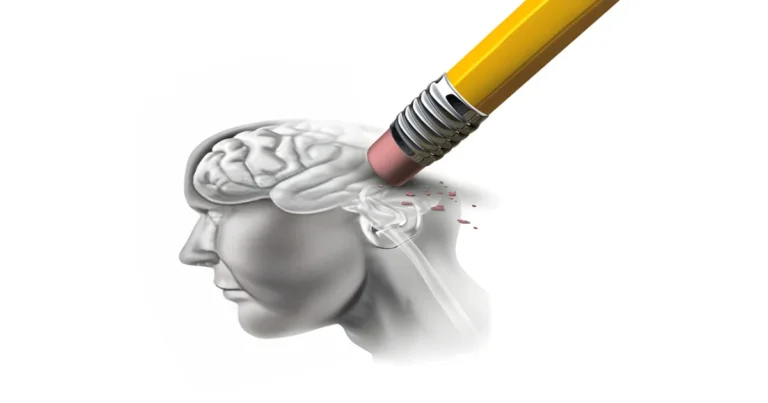

The door that closed: When memories are blocked, not lost

M.M.’s retrograde amnesia did not result from the total destruction of his memories, as one might expect after a severe brain injury, but rather from a disruption in the retrieval mechanisms. His memories often persisted in the form of latent traces, still present but inaccessible, as though a door had closed between them and his conscious awareness.

Researcher Lucchelli and his colleagues from the Department of Neurology at Ospedale S. Carlo Borromeo in Milan propose an intriguing hypothesis to explain this phenomenon. They suggest that the amnesia was caused by a transient disruption of neuronal connections in what they call “neural matrices”, complex networks responsible for organizing and accessing autobiographical memory. This disruption could be compared to a partially corrupted hard drive: the data remains intact, but the access system is temporarily faulty. However, M.M.’s case demonstrates that these neural matrices are not irreversibly damaged. The moment he regained his memories is as fascinating as their loss. A simple technical mistake during his tennis match acted as a mnemonic trigger, activating procedural memories related to the sport. These procedural memories, being less vulnerable than autobiographical memories, likely served as a bridge to reawaken more complex personal memories.

This spontaneous reactivation underscores the powerful connection between memory and context.

Our brain operates associatively, meaning that memories are not stored in isolation but are woven into a complex network in which senses, emotions, and the environment play binding roles. A scent, a melody, or even a texture can revive memories by triggering the same brain regions that initially encoded them.

This phenomenon mirrors the experience described by Marcel Proust in In Search of Lost Time, where the taste of a madeleine dipped in tea brings buried childhood memories to the surface. In his novel, the taste of the madeleine acts as a key that opens the doors to forgotten memories. This simple taste, tied to a specific emotion and context, triggers a cascading reactivation of buried recollections, reintroducing the narrator to a past he believed lost. While Proust’s description is metaphorical, it strikingly reflects the neuroscientific mechanisms at play in M.M.’s case.

For M.M., it wasn’t the taste of a madeleine, but a rich, multisensory environment, the tennis match, that served as the mnemonic trigger. The repetitive gestures of the game, the familiar sound of the ball hitting the racket, the physical sensations tied to exertion, and even the smell of the court or the ambient light would have collectively activated dormant neural networks. These networks, associated with his procedural memory and past experiences in athletic competition, would have provided an entry point to restore access to the autobiographical memories that had been temporarily lost.

Memory’s hidden pathways: How context resurrects the past

This phenomenon underscores the crucial role of contextual cues in human memory. Unlike voluntary retrieval, which is often cognitively demanding, multisensory stimulation appears to take more direct routes, activating deep neural circuits often tied to emotionally charged memories. In M.M.’s case, immersion in a familiar context, his tennis match, enabled his brain to bypass blockages, gradually rediscovering a previously inaccessible path. Each movement, each sensation of the game acted as a subtle trigger: one element calling up a fragment of memory, which in turn triggered another, setting off a cascade of reactivations. The context thus transformed into a revelatory key, capable of reopening the doors to the neural activity necessary to “reread” these once-buried memories, as if the brain were piecing together a long-forgotten puzzle, one piece at a time.

This interaction between context and memory also highlights the importance of active sensory immersion. It was not merely the sight of a tennis court that triggered the process, but the act of playing itself, engaging both physically and mentally in an activity strongly linked to his past. This complete reactivation of memories, first related to tennis and then extending to his personal history, emphasizes the interdependence between procedural memory, emotions, and autobiographical memory. It also showcases the brain’s remarkable ability to use intact fragments to reconstruct more complex sets of memories.

In this way, much like Proust’s madeleine, a simple tennis match revived for M.M. much more than mere memories; it rekindled an entire network of buried experiences. This case dramatically highlights the brain’s incredible plasticity, one of its most extraordinary capabilities.

Even when its connections appear damaged, locked, or fragmented, the brain remains capable of reorganizing its networks, circumventing obstacles, and, at times, reviving connections once thought lost forever.

In M.M.’s case, it was powerful contextual cues, combined with the immersive experience of the game, that acted as keys to unlocking his memory. But why did these memories resurface so suddenly? The answer seems to lie in the strength of the context and emotions. When an experience is marked by emotional intensity or deep physical involvement, it becomes more firmly anchored in neural circuits, making it more accessible for reactivation. It’s as though emotion engraves the memory more deeply into the marble of our brain.

This case extends beyond a simple clinical anecdote; it offers a fascinating glimpse into the workings of human memory and opens unexpected possibilities. If contextual cues or specific environments can awaken forgotten memories, why not harness them to develop new therapies? Therapies that rely on immersive activities, familiar contexts, or emotional stimulation to revive these “buried treasures” that are our memories. Understanding which neural circuits are activated during these resurges could provide a solid foundation for targeted interventions, utilizing brain plasticity to combat memory disorders.

These observations, full of hope, suggest that memory is not a hermetic vault but rather a wild garden, sometimes overgrown, sometimes dormant, but always capable of blooming with the slightest breath. M.M.’s story is a striking demonstration of the resilience of our brain. What we believe to be irreversibly lost, erased beyond recall, may, in some surprising way, return to us. Our brain, astonishingly rich in unsuspected resources, holds in its most fragile corners the ability to revive memory. A breath, a place, an emotion, and suddenly, everything resurfaces like a long-buried treasure. The mystery remains vast, and with it, hope continues to grow.

References: