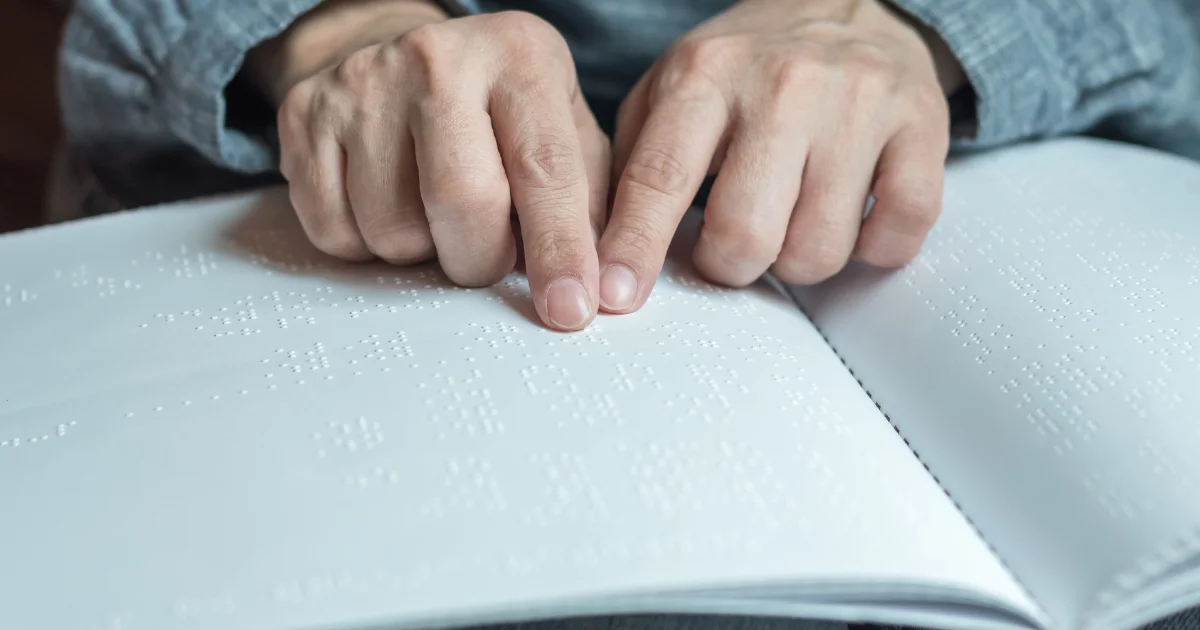

Braille: How the brain recognizes words through touch

Reading without ever seeing a letter may sound counterintuitive. In most societies, written language is inseparable from vision: pages, screens, symbols scanned by the eyes. Reading appears so tightly bound to sight that imagining it in any other form seems almost impossible.

However, braille challenges this assumption. As their fingers glide across lines of raised dots, blind readers truly read, not metaphorically, but in the strictest neurological sense. Their brains recognize words, structures, and written language. They do not compensate for the absence of vision. They read.

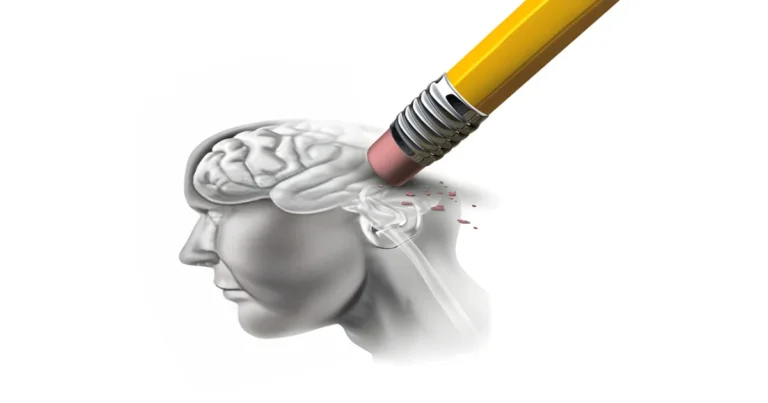

Cognitive neuroscience has gradually revealed this striking fact. When reading braille, the brain recruits neural circuits remarkably similar to those used in visual reading. The same regions specialized in identifying written words become active, as if the brain were largely indifferent to the sensory channel through which information enters. What matters is not the eyes or the fingers, but the symbolic structure of language itself.

Reading therefore appears in a new light. It is not a visual function, but a cerebral capacity to recognize and interpret written forms, regardless of the sensory modality involved. Braille is far more than a tactile writing system. It offers a unique window into how the human brain encodes words, even in the complete absence of images.

🔗Read also: Beyond words: can we think without words?

How the brain recognizes words without visual input

For a sighted person, reading feels almost automatic. The eyes move across lines, and words emerge with little conscious effort. Beneath this apparent simplicity lies a highly specialized neural network, largely located in the left hemisphere. At its core is a small region of the occipitotemporal cortex, commonly referred to as the visual word form area.

Despite its name, this region does not merely recognize letters as visual shapes. It is sensitive to the organization of written language itself: letter order, recurring combinations, word familiarity, and morphological structure. Over time, it learns the statistical regularities of written language, enabling rapid and efficient word identification. This specialization is not present at birth. It emerges through reading acquisition and relies on a process known as neuronal recycling, whereby brain circuits initially devoted to visual form recognition are reorganized to support a culturally recent skill.

This hypothesis has been rigorously tested in blind readers. When a blind individual reads braille, the same left occipitotemporal region becomes active, even though no visual input is available. More strikingly, its activity varies according to linguistic properties of words, such as usage frequency or internal structure. The brain is therefore not merely responding to finger contact with the page. It is processing the orthographic identity of the word.

These findings demonstrate that this region is not fundamentally visual. It is specialized for processing written language forms, regardless of the sensory pathway through which they are perceived. Touch is not a fallback solution. It provides direct access to the brain’s word recognition system.

This does not imply that braille reading is identical to visual reading. Touch imposes its own constraints. Information is gathered more sequentially and more slowly, engaging additional regions involved in temporal and spatial integration. Nevertheless, despite these differences, the core process of written word recognition relies on a largely shared functional network. Reading emerges as the brain’s capacity to process linguistic symbols, rather than a function tied to vision alone.

🔗Explore further: When nature becomes a classroom

From fingers to words: the neural pathways of braille

Reading braille is not a passive act. Fingers move slowly along the line, exploring each character point by point. Unlike vision, which can capture multiple letters or even words in a single glance, touch enforces a strictly sequential mode of access. Each unit of information is acquired locally over time. This form of reading strongly engages the somatosensory cortex, which processes tactile input, as well as the posterior parietal cortex, a key region for spatial organization and sequencing. Together, these regions transform a series of local sensations into a coherent structure that conforms to the rules of written language.

This transformation step is crucial. It partly explains why braille reading is slower than visual reading. Touch imposes sequential access, whereas vision allows for a more global intake. However, this difference in speed does not alter the nature of the process. At the neural level, braille fully engages the mechanisms of reading. It is not a tactile decoding followed by linguistic translation, but a genuine recognition of written words.

Once the information is structured, the central reading circuits take over. Brain imaging studies show that in expert braille readers, frontotemporal networks involved in written language are activated in ways comparable to those observed in sighted readers. The brain builds stable orthographic representations. It encodes letter positions, morphological regularities, and internal word structure. These representations are essential for writing, spelling, syntactic manipulation, and the production of complex texts.

This is where the comparison with audio becomes particularly informative. Text to speech technologies provide rapid and efficient access to meaning and are invaluable for everyday information. However, listening to a text is not the same as reading it. At the cognitive level, audio primarily engages oral language comprehension circuits, which process language as a continuous auditory stream. The brain is not required to analyze written structure or encode orthographic form. This difference has significant consequences. Without exposure to written language, it becomes difficult to build stable orthographic representations, master written syntax, or develop certain metalinguistic skills. Neuroscience shows that reading, whether through braille or vision, engages specific operations distinct from those involved in listening. Braille does more than transmit linguistic content. It provides access to language in its written form.

In people who are blind from an early age, this organization is embedded within broader cortical plasticity. Deprived of visual input, the occipital cortex does not remain inactive. It is recruited for higher level cognitive functions, particularly language and verbal memory. During braille reading, regions traditionally labeled as visual actively participate in linguistic processing. This is not an opportunistic reassignment, but a reorganization guided by the computational demands of reading and the symbolic structure of written language.

Braille therefore stands as far more than a technical alternative to audio. It is a genuine literacy tool, capable of supporting the same fundamental cognitive operations as visual reading and allowing the brain full access to written language, with its forms, rules, and memory. By revealing how the brain can read without seeing, braille reminds us that reading does not depend on a particular sense, but on the human brain’s capacity to recognize, organize, and assign meaning to symbols. An extraordinary capacity, deeply abstract and remarkably flexible, that continues to shape our relationship with words, regardless of the pathways through which they reach us.

References

Amedi, A., Raz, N., Pianka, P., Malach, R., & Zohary, E. (2003). Early “visual” cortex activation correlates with superior verbal memory performance in the blind. Nature Neuroscience, 6(7), 758–766.

Dehaene, S., & Cohen, L. (2007). Cultural recycling of cortical maps. Neuron, 56(2), 384–398.

Reich, L., Szwed, M., Cohen, L., & Amedi, A. (2011). A ventral visual stream reading center independent of visual experience. Current Biology, 21(5), 363–368.

Siuda-Krzywicka, K., Bola, Ł., Paplińska, M., Sumera, E., Hańczur, P., Szwed, M., & Wróbel, A. (2016). Massive cortical reorganization in sighted Braille readers. eLife, 5, e10762.

Sara Lakehayli

PhD, Clinical Neuroscience & Mental Health

Associate member of the Laboratory for Nervous System Diseases, Neurosensory Disorders, and Disability, Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy of Casablanca

Professor, Higher School of Psychology