How social media is reshaping our relationship with the body

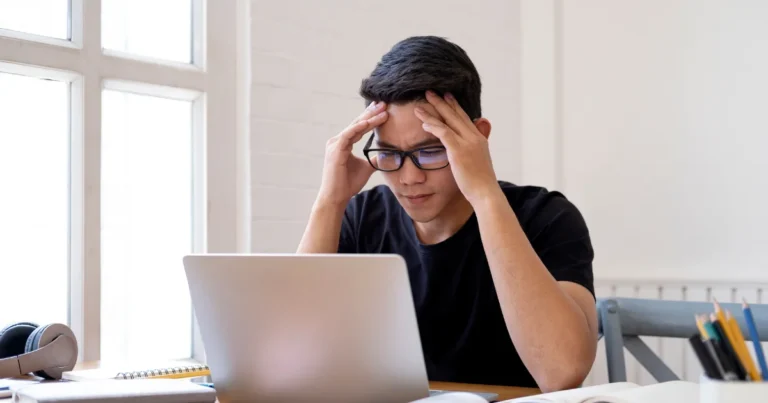

Never before has the body been so exposed, scrutinized, compared, and performed as it is in the age of social media. In just a few years, digital platforms have profoundly transformed our relationship with visibility, appearance, and self-representation. Behind the filters, choreographed poses, curated stories, and Instagram-perfect snapshots lies a deeper shift: a radical transformation of body image and self-image, two foundational concepts in the field of psychomotricity.

The body is not merely a visible object. It is experienced, felt, inhabited. It underpins identity, anchors self-assertion, and mediates our connection with others. In the digital age, however, the body tends to be reduced to an externalized image, shaped by social expectations and the gaze of others, often at the expense of inner bodily awareness.

This article explores how social media disrupts, or in some cases, reinforces, the psychomotor development of self-image. Key psychomotor concepts such as body image, body schema, embodied self-esteem, sensorimotor experience, and emotional regulation will be discussed, using clinical cases and contemporary social observations.

Body image and self-image: A gradual and embodied construction

In psychomotricity, body image refers to the mental and emotional representation of one’s own body. It encompasses perceptual, motor, emotional, social, and symbolic components. It differs from the body schema, which pertains to sensation, proprioception, and postural integration.

Self-image is broader. It includes body image but also encompasses one’s perceived abilities, worth, and personality. It is rooted in the body, as self-awareness initially emerges through sensory and motor experiences.

Take, for example, an adolescent undergoing psychomotor therapy for school refusal. He reports feeling “out of place in his body,” wears oversized clothing, avoids mirrors, and refuses group physical activities. Yet on social media, he posts retouched photos of himself looking confident, stylized, almost unreal. This discrepancy highlights a growing dissociation between the lived body (often perceived as painful or insecure) and the represented body (conforming to social and aesthetic norms).

🔗 Read also: The brain rot effect: Instant content and the erosion of our mental functions

Social media: A distorted mirror of the body

On platforms like TikTok, Instagram, and Snapchat, the body is omnipresent, yet rarely authentic. It is displayed, filtered, stylized, and performed. This hyperexposure significantly alters bodily references, especially among adolescents navigating identity formation.

When the lived body and the displayed body drift apart

In clinical practice, we increasingly see children and adolescents experiencing a disconnect between their physical sensations and their online personas. This distortion may lead to body image disorders (shame, fixation on perceived flaws), sensory disconnection (loss of proprioceptive, kinesthetic, and tactile awareness), and emotional dysregulation (difficulty managing internal tension).

Consider a 14-year-old girl who refuses to remove her shoes, dance, or practice yoga during sessions, yet posts daily dance videos on TikTok. The online environment allows her to feel in control of her image through editing and performance. In contrast, real-life interactions trigger a sense of bodily intrusion caused by sensory and emotional overstimulation.

The standardization of bodies and the loss of sensory uniqueness

Aesthetic filters, stereotyped poses, choreographed movements, and body trends promote uniformity in how bodies are displayed. Psychomotor observations reveal a decline in creative movement and sensory richness: the body becomes something to sculpt for aesthetics, not an intimate space to inhabit. This standardization dulls motor spontaneity and favors rehearsed gestures over genuine expression.

🔗 Explore further: Repressed and reloaded: Psychoanalysis in the age of social media

Bodies in distress, wounded self-images: clinical manifestations

These tensions manifest in many ways during psychomotor sessions. They affect muscle tone, gross and fine motor skills, emotional expression, and social engagement. Many young people active on social media struggle to regulate their inner states: they exhibit hypersensitivity, muscular tension, sleep disturbances, restlessness, or withdrawal.

One example is a 12-year-old boy highly engaged on YouTube who presents with constant jaw tension, a withdrawn posture, and hyperactivity when stimulated. His body is emotionally overloaded, yet he lacks the tools to express or contain his inner turmoil.

Other teens completely reject real-life physical activities like dance, sports, touch, or roleplay, while deeply investing in their digital avatars. In sessions, this manifests as bodily inhibition, poor coordination, and dissociation between movement and intent. Their focus on appearance can fragment the body image, showing the face, hiding the stomach, correcting the silhouette, leading to a fractured sense of bodily unity, which is crucial for identity construction.

Reclaiming an Embodied Self-Image

Psychomotricity plays a crucial role in addressing these challenges. It provides a space for reconnecting with the lived body, through slowness, care, and sensory exploration. Working on muscle tone and relaxation, especially via psychomotor relaxation techniques, helps children and teens reconnect with internal sensations, ease tensions tied to social appearance, and establish a sense of bodily safety.

Engaging the body in non-competitive activities, free dance, sculpting, mime, or sensory pathways, restores the joy of movement and nurtures a non-judgmental relationship with the body. This is paired with symbolic integration: through body drawing, roleplay, or embodied storytelling, individuals learn to name, express, and integrate what they physically feel.

Supporting families and educators is often essential. Psychoeducational guidance on digital habits, the distinction between image and identity, and the difference between displayed and felt body can help cultivate a more compassionate and coherent self-perception.

🔗 Discover more: Who am i online? Rethinking identity in the social media era

The construction of self-image is a gradual, sensitive, deeply embodied process. In the era of social media, this process is strained by the dominance of external validation, identity fragmentation, and the standardization of bodily representations.

As a discipline rooted in the lived body, psychomotricity offers a therapeutic path to help individuals, young and old, reclaim their embodied self. Restoring a sensitive, unique connection to one’s body lays the groundwork for a self-image that is more stable, more free, and ultimately, more authentic.

References

Ajuriaguerra, J. de (1980). L’image du corps : essais sur les fonctions de l’image corporelle. Paris : Gallimard.

Bruchon-Schweitzer, M. (2002). Psychologie de la santé : modèles, concepts et méthodes. Paris : Dunod.

Dolto, F. (1984). L’image inconsciente du corps. Paris : Seuil.

Ehrenberg, A. (1998). La fatigue d’être soi : dépression et société. Paris : Odile Jacob.

Erikson, E. (1972). L’identité, la jeunesse et la crise. Paris : Flammarion.

Blaise Pierrehumbert (2003). Le Premier Lien. Théorie de l’attachement. Paris : Odile Jacob.

Le Breton, D. (2001). La sociologie du corps. Paris : PUF.

Le Breton, D. (2014). Disparaître de soi : une tentation contemporaine. Paris : Métailié.

Maigret, E., & Monnoyer-Smith, L. (2003). Sociologie de la communication et des médias. Paris, Éditions Armand Colin,

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1945). Phénoménologie de la perception. Paris : Gallimard.

Turkle, S. (2011). Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. Basic Books.

Saad Chraibi

Psychomotor Therapist

• A graduate of Mohammed VI University in Casablanca, currently practicing independently in a private clinic based in Casablanca, Morocco.

• Embraces a holistic and integrative approach that addresses the physical, psychological, emotional, and relational dimensions of each individual.

• Former medical student with four years of training, bringing a solid biomedical background and clinical rigor to his psychomotor practice.

• Holds diverse professional experience across associative organizations and private practice, with extensive interdisciplinary collaboration involving speech therapists, psychologists, neuropsychologists, and other healthcare professionals.

• Specializes in tailoring therapeutic interventions to a wide range of profiles, with a strong focus on network-based, collaborative care.

• Deeply committed to developing personalized therapeutic plans grounded in thorough assessments, respecting each patient’s unique history, pace, and potential, across all age groups.