Inside the translator’s mind: A psycholinguistic view of translation

Translation is certainly a linguistic act and an extra linguistic activity. However, it is above all a psycholinguistic process and, by its very nature, a cognitive one. The translational act involves a number of psycholinguistic mechanisms and tasks that allow the apprehension and re expression of word meaning and sentence meaning from a source language into a target language.

The aim of this article is to examine what takes place inside the translator’s black box. What are the mental and cognitive mechanisms that underpin and govern the operation of translation and the act of translating? What are the neurobiological foundations that support translational activity?

Psycholinguistics of the translational act

Cooperation between translation specialists and psycholinguists is beneficial for several reasons.

First, the expected outcomes of this collaboration can provide translation professionals and teachers with valuable tools to enrich their theoretical reflections and practical approaches, including courses, exercises, and analysis of production errors, with the goal of training translators who are more reliable and more efficient.

Second, it allows examination, within the translational act, of the cognitive procedures that, through practice and training, may lead to a degree of automatization in the translator. This could imply a reduction in the mental workload required to carry out a translation, namely the cognitive cost.

Third, it enables the modelling of translational activity by describing and explaining its psycholinguistic functioning, as well as the stages and tasks involved.

Psycholinguistics is concerned both with the translated text, the product of translation, and with the translator as a cognitive entity and a factor of crucial importance in the translational act, whose mission is to facilitate the communicative process of translation, involving the sender or author, the translator, the message or translated text, and the receiver.

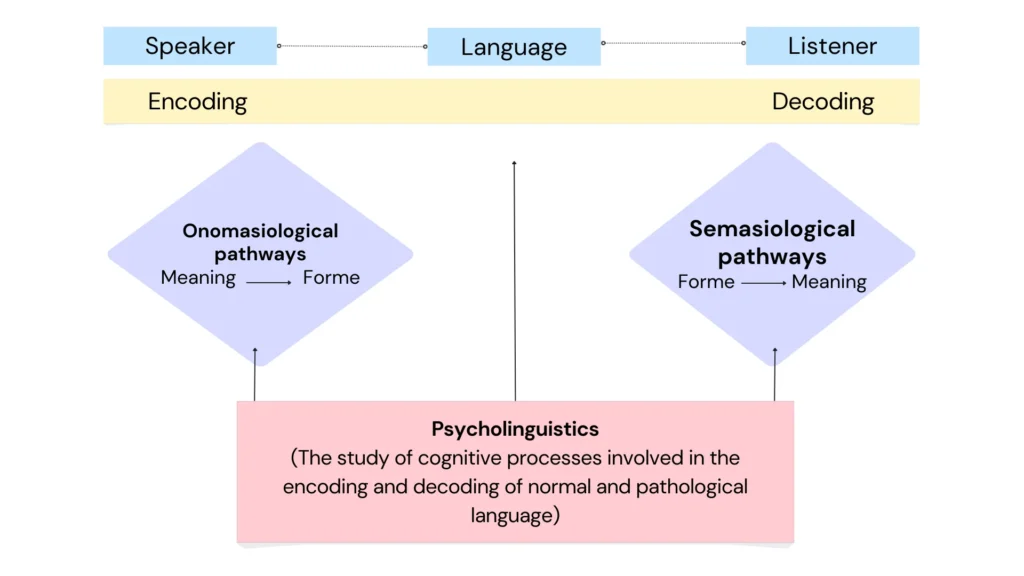

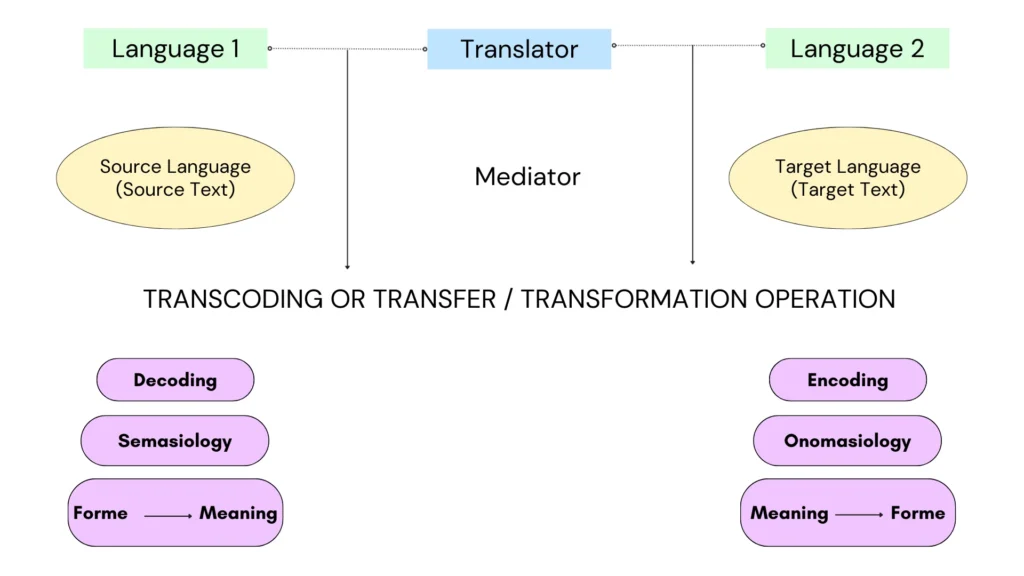

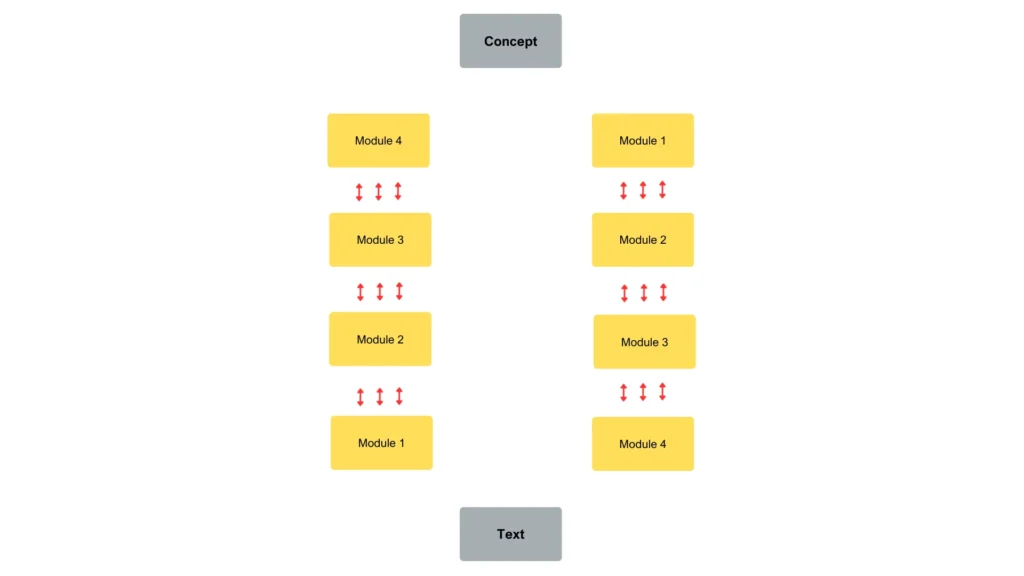

Translation is a psycholinguistic process carried out by a mediator, the translator or interpreter, during the transfer phase as defined by Nida. It involves cognitive mechanisms and follows two distinct pathways. The first is an onomasiological pathway, from meaning to form. The second is a semasiological pathway, from form to meaning.

This definition reflects the classic definition of the object of psycholinguistics, namely the scientific study of encoding and decoding processes during communication, insofar as they link message states to communicator states. Charles Osgood and Thomas Sebeok (1954), Psycholinguistics: A Survey of Theory and Research Problems, page 4.

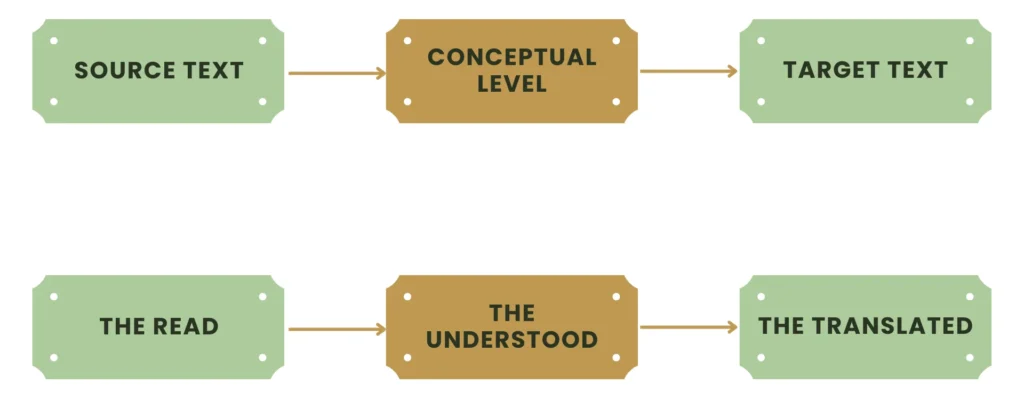

The first schema below delineates the field of psycholinguistics, and the second identifies the elements involved in the construction of the translational act.

A cognitive model of translation workflows

The translational act can be conceived as a problem situation that must be solved. The translator’s strategy is governed by cognitive factors. Translational activity consists of a series of stages representing cognitive processing tasks that allow the decoding and encoding of translational material.

Starting from the psycholinguistic model proposed by Willem Levelt (1989) in Speaking: From Intention to Articulation, further developed by Juan Segui and Ludovic Ferrand (2000), and drawing on a set of neuropsychological studies published in the specialized journal of translation studies META, volume LII, issue 1, 2007, a special issue devoted to cognitive sciences and translation studies, we attempt to propose a psycholinguistic model of the translational act.

The core processing stages of translation

Like any inter communicational activity, the translational act is the result of a decoding process involving perception and comprehension, and an encoding process involving production and formulation.

Written Translation

The written translational act results from the combined action of three organic systems: the perceptual system, visual and auditory, the meaning system, and the output system.

Stage 1: Reading

Reading is both an oculomotor and a cognitive activity. It consists in the visual perceptual recognition of the source text. It is the means through which the reader or translator perceives the information contained in the text, which will then be processed within the memory system. The translator therefore carries out several tasks.

The first task is word identification. This involves grammatical decoding, semantic and syntactic, of lemmas, and phonological decoding of lexemes.

The second task is lexical segmentation. This takes into account the phonemic, syllabic, morphemic, graphemic, and lexical composition of simple and compound words.

The reading strategy that mobilizes identification and segmentation tasks requires access to the translator’s mental lexicon, an internal dictionary in which knowledge about words in the source language, and also in the target language, is represented.

According to Alexandra Kosma (2005), the reader translator adopts reading strategies that differ from those of a simple reader, because the translator appears to use strategies that prepare the reformulation of the meaning of the utterance. These strategies vary according to the type of text to be translated, the translator’s level of expertise, and other factors. Subjects who produce a so called word for word translation, translating by seeking only word and meaning correspondences, display an almost linear ocular process. By contrast, subjects who adopt a more synthetic, semantic strategy show a more exploratory reading path.

Several types of reading strategies can thus be identified. Studious reading aims to extract the maximum amount of information from the text. Skimming is used when the reader seeks only to grasp the essential elements. Selective scanning is employed when the reader searches for a specific piece of information. Action oriented reading is adopted when the reader must perform an action based on a text containing instructions. Oralized reading consists in reading a text aloud.

Stage 2: Attention

Attention is the capacity an individual has to consciously take control of their mind in order to focus cognitive resources on a particular thought or object among several others. This implies rejecting a number of elements in order to manage the remaining ones effectively.

Attention is linked to the way the cognitive system processes information. It is a mental activity associated with reading and plays an important role at all stages of the translational process.

It is therefore necessary to study how the translator manages attentional resources during the different stages of translation or when handling certain types of difficulty, since several types of errors appear to result from inadequate allocation of attention.

In what ways does attention influence translator reliability and performance? What effects does attention have on the mental workload required to accomplish the translational act? Can strategies for regulating attention be proposed according to the degree of translational difficulty and the volume of work to be carried out?

Researchers distinguish between automatic attentional processes, which are fast, parallel, and effortless, and conscious attentional processes, which are slow, sequential, and strategic, governed by control functions and motivation.

Translational activity requires particularly sustained attention, considerable physical, mental, and nervous endurance, and multiple distinct and simultaneous efforts that may lead the translator, especially the interpreter, to saturation and to errors.

Stage 3: Deverbalization and Conceptualization

Translation is work on the message and on meaning. Whether oral or written, literary or technical, the translational operation always comprises two components: understanding and saying. After understanding, the task is to deverbalize and then to reformulate or re express.

The task of deverbalizing the text aims to translate it mentally, that is, to provide it with a conceptual representation. This is a cognitive representation of a non linguistic nature, a preverbal representation. Deverbalization also involves disambiguating the semantic and conceptual content of the source text. It consists in stripping away the linguistic surface of the initial text.

Stage 4: Memorization

Working memory, short term or episodic memory, retains the conceptualized or deverbalized information extracted during the translator’s reading of the source text. Long term memory stores the various bodies of knowledge and concepts used in interpreting deverbalized information.

The most relevant concepts in the text are transferred to short term memory, or working memory, where they are processed. This memory retains the most pertinent information to ensure continuity of comprehension.

The central processor then begins to process this information, drawing on long term memory networks that relay to short term memory information related to the notions and concepts evoked by the discourse, as well as situational information. This information stems from diverse forms of knowledge accumulated by the interpreter over the course of life, including encyclopedic knowledge.

Not all information retrieved from long term memory is relevant, and only a portion can be used. This is where inhibition intervenes, acting as a modulator of activation and a filter against irrelevance.

According to Baddeley’s model (1993), the central executive system performs several functions, including inhibition of automatic responses or irrelevant information, activation of information in long term memory, planning of activity, and allocation of resources. It constitutes the attentional component of working memory, coordinating, selecting, and controlling processing operations. Under its control, specialized components known as the phonological loop and the visuospatial sketchpad temporarily store verbal information and visual or spatial information respectively. To maintain information in these subsystems, mental rehearsal is required. Also under the control of the central executive, the episodic buffer integrates conceptual, semantic, visuospatial, and phonetic information from long term memory and from the two subsystems into a unified representation. It serves as a major interface for managing information between working memory and long term memory. Experimental studies by Baddeley (2001) have confirmed these functions. These components manage information that is flexible and constantly changing, whereas long term memory provides stable and crystallized information. Cognitive psychology research shows that complex intellectual activities such as reading comprehension, written text production, problem solving, mathematical reasoning, and second language learning depend functionally on this structure.

Stage 5: Reformulation of Meaning

The translational operation involves a search for meaning followed by reformulation, also called re verbalization or re expression, through the establishment of equivalences.

This task consists in reformulating, in the target language and target text, what has been understood from reading the source text. For meaning to be re materialized in linguistic form, it must be re verbalized.

Reformulating meaning involves a specific form of writing activity. Although constrained by the author’s intended meaning and expressed content, the translator must develop their own writing strategy, taking into account the communicational and situational parameters governing the translational act, particularly in textualization, including format, genre, and rhetorical choices. Writing the translation can be considered a problem that requires a solution, a series of decisions. The translated product then becomes the object of re examination and revision.

🔗Read also: Beyond words: can we think without words?

Oral Translation, Interpreting

Oral translation, interpreting, is carried out through the following stages.

First, auditory perception. This involves hearing the source message and extracting a conceptual, deverbalized representation.

Second, attention and conceptual memorization. Oral translation is characterized by the simultaneous execution of auditory perception, comprehension, and reformulation. This requires vigilant attention and effective memorization, resulting in a high cognitive cost, rapid execution speed, verbal fluency, automatization, and intense verbal auditory processing. The task is to retain the source message, memorizing its deverbalized content over the time span of the speaker’s utterance, which implies conceptualization and the transition from immediate memory to semantic long term memory.

Third, reformulation. This involves re expressing the source message in the target language through grammatical and phonological encoding, lemmas and lexemes, using the internalized mental lexicon. This results in a syntactic and phonological representation of the perceived auditory signal, including co articulatory gestures, acoustic cues, syllabic structure, and prosodic features.

Fourth, articulation. The translated output is articulated through the phonatory system. In a successful translation, the conceptual content associated by the translator with the target text must correspond to that intended by the author of the source text.

Is translational processing serial or interactive?

Three types of psycholinguistic processing models can be envisaged for translation: a serial model, a cascade model, and an interactive model.

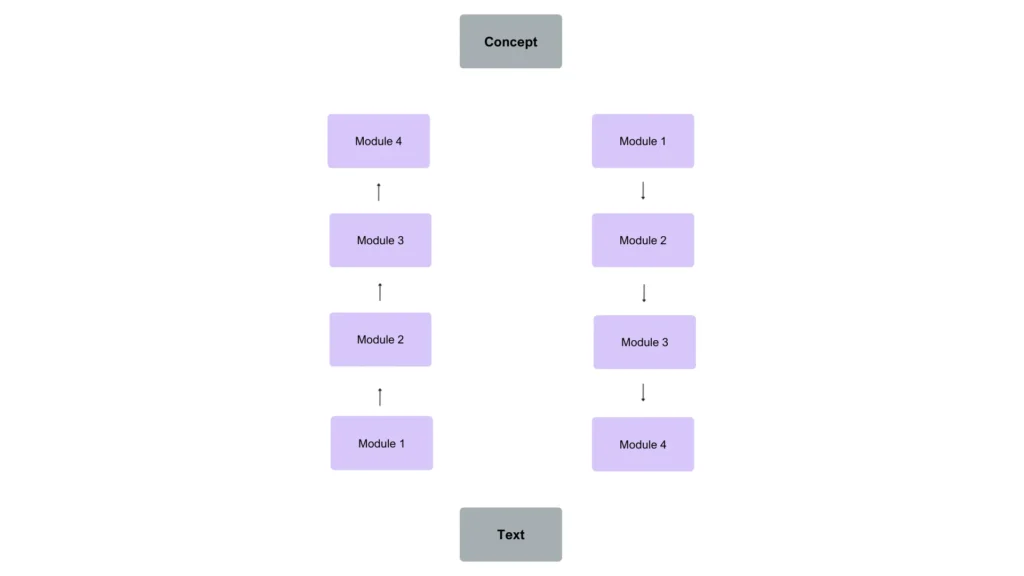

The Serial Model

In this model, the transmission of information from one component to another within translational activity occurs in a strictly sequential manner. The processing of a particular type of information, whether visual, auditory, or phonological, must be completed before processing begins at the next level.

During the decoding phase, perception and comprehension, each level of representation is derived entirely from the immediately lower level in a bottom-up serial procedure. Conversely, during the encoding phase, production or reformulation, each level of representation is derived entirely from the immediately higher level in a top-down serial procedure.

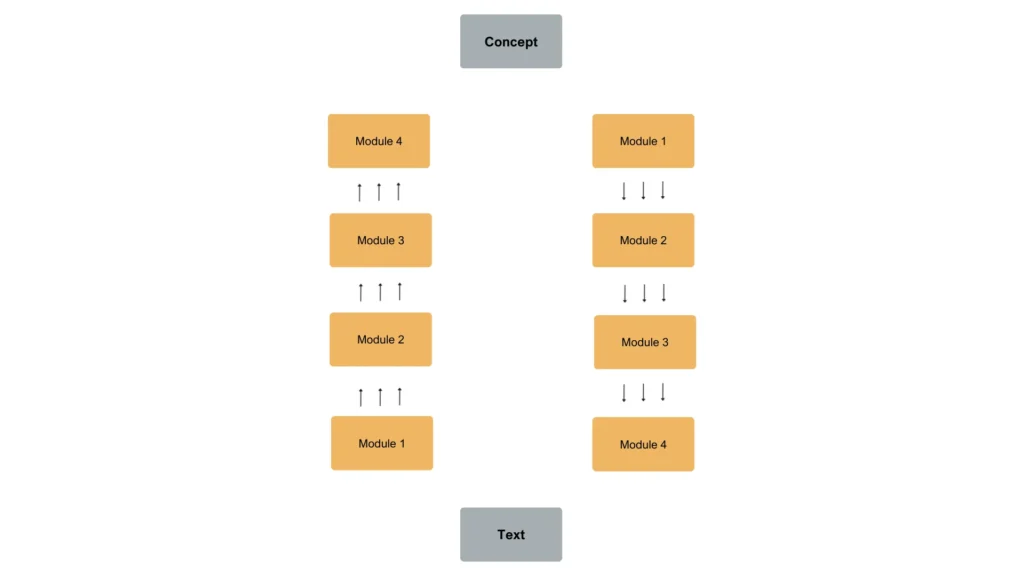

The Cascade Model

In this model, the principle of processing autonomy in the translator is maintained, while allowing different submodules to operate in parallel. Information is transmitted between submodules in partial units or “packets.”

A submodule may continue processing a given type of information while simultaneously transferring fragmentary information to another submodule, which can then use it to carry out its own processing.

The Interactive Model

In the interactive model, the functioning of a particular component does not depend solely on information coming from the immediately lower level, as in perception and comprehension, or the immediately higher level, as in production or reformulation.

Information from higher syntactic and semantic levels, for example during lexical processing, may directly influence the processes involved in word identification.

As Segui (1992) points out, the psycholinguistic processes involved in translation can be described as “more or less modular.” The relevance of the modularity hypothesis depends in particular on the nature of the psycholinguistic process under consideration and, more specifically, on its position within the processing system.

A process is more likely to be modular when it is early, that is, low-level. By contrast, later processes involved in translational activity tend to be more open, non-encapsulated, and permeable to information from multiple sources.

The Translator’s Brain

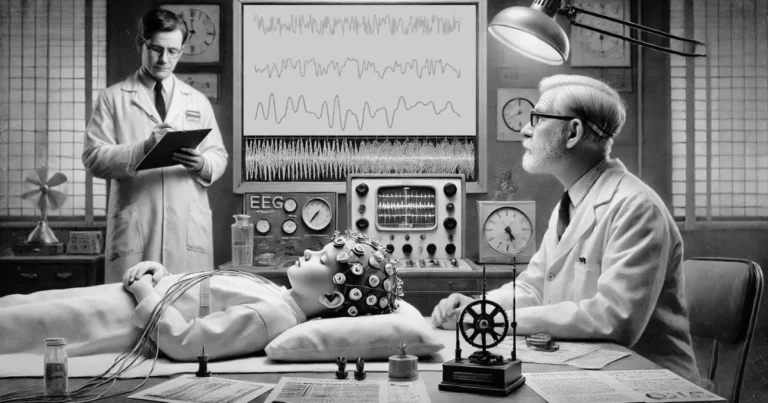

The psycholinguistic tasks involved in translation are supported by neurocerebral structures organized into specialized subcomponents with specific functions and inter neuronal connections.

Advances in functional brain imaging techniques, including functional magnetic resonance imaging, positron emission tomography, functional magnetoencephalography, and electroencephalography, have made it possible to visualize the chronological and spatial stages of cognitive processing in the human brain.

Cognitive operations involved in translation show a progression from occipital activation related to vision, and auditory cortex activation, through parietal and temporal regions including Wernicke’s area, toward frontal regions including Broca’s area in the left hemisphere. All regions of the language network are activated during translation. This supports an associationist rather than a strictly localizationist conception of cerebral processing in translation.

The translator or interpreter is a bilingual or polyglot individual with linguistic awareness. This awareness constrains translational processing. At the phonological level, phonological awareness influences perceptual processing, which is subject to perceptual filtering and may sometimes result in phonological deafness. The translator may adopt an ignoring strategy, disregarding phonological properties of the source language, or an assimilation strategy, assimilating them to those of the native language.

Switching between languages during translation is ensured by control and inhibition strategies, particularly in cases of interference between linguistic codes.

Is the translator equivalent to two monolinguals in one brain? The answer is no. Translator performance depends on the level of mastery of the second language and on learning conditions, particularly age of acquisition, which is linked to brain plasticity and the remodeling of neural structures involved in language acquisition and use.

Another important issue deserves investigation, namely the pathological dimension of translation. This concerns the difficulties faced by a translator or multilingual individual suffering from brain lesions or neurocerebral deterioration, such as aphasia.

🔗Discover more: Braille: How the brain recognizes words through touch

References

BADDELEY, A. D. 1993: La mémoire humaine. Théorie et pratique, Grenoble, Presses Universitaires de Grenoble.

BALLIU, Ch. 2007 : Cognition et déverbalisation, Meta, LII, 1.

CARRON, J. 2008: Précis de psycholinguistique, P.U.F.

DORTIER, J-F. 2004 : Le Dictionnaire des Sciences Humaines, EDITIONS SCIENCES HUMAINES, DELTA, Beyrouth, Liban.

KELLER, E. 1985: Introduction aux systèmes psycholinguistiques, Gaëtan Morin éditeur, Canada.

KOSMA , A. 2007: le fonctionnement spécifique de la mémoire de travail en traduction, Meta, LII, 1.

LADMIRAL, J.-R. 2002: Traduire : théorèmes pour la traduction, Paris, Gallimard.

LEVELT, W.J.M. 1989: Speaking : from Intention to Articulation, Cambridge, MIT Press.

MOESCHLER, J. & AUCHLIN, A. 1997: Introduction à la linguistique contemporaine, Armand Colin/Maison, Paris.

OSGOOD, Ch. & SEBEOK, Th. 1954: Psycholinguistics : A survey of theory and research problems, Indiana University Publications in Anthropology.

PAPAVASSILIOU, P. 2007: Traductologie et sciences cognitives : une dialectique prometteuse, Meta, LII, 1.

PIOLAT, A. 2007: Approche cognitive de l’activité rédactionnelle et de son acquisition : le rôle de la mémoire de travail, Meta, LII, 1.

POLITIS, M. 2007: L’apport de la psychologie cognitive à la didactique de la traduction, Meta, LII, 1.

SEGUI, J. & LUDOVIC, F. 2000: Leçons de parole, Editions, Odile Jacob, Paris.

TATILON, C. 2007: Pédagogie du traduire : les tâches cognitives de l’acte traductif, Meta, LII, 1.

Mourad Mawhoub

Full Professor of Linguistics, Hassan II University of Casablanca

State Doctorate (Doctorat d’État) in Linguistics and Psycholinguistics, Cadi Ayyad University, Marrakech, 2001.

PhD (Nouveau Régime) in Linguistics and Phonetics, Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris III, 1992.

Postgraduate Diploma (DEA) in Linguistics and Experimental Phonetics, Laboratory of Phonetics, Université Paris III, 1987.

Former Dean of the Faculty of Letters and Human Sciences, Ain Chock, Hassan II University of Casablanca.

Former Director of the Academy of Traditional Arts, Hassan II Mosque Foundation, Casablanca.

Author of numerous peer-reviewed publications in linguistics, experimental phonetics, psycholinguistics, and neurolinguistics.