The hidden language of smoking in cinema

Sometimes, all it takes is a static shot, low angled lighting, and a lit cigarette for that elusive urge to smoke to surface. In cinema, the cigarette is almost never a simple prop. It is a language.

For decades, Hollywood constructed a visual grammar in which smoking conveys something precise: freedom, danger, seduction, intelligence, or inner fracture. It is this symbolic charge, far more than the product itself, that becomes anchored in the spectator’s mind.

How smoking defines a character without words

In classic Hollywood cinema, the cigarette often serves to define a character within seconds, without dialogue. Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca (1942) smokes almost constantly. The cigarette accompanies his apparent cynicism, his disillusionment, and his emotional restraint. It is not there to show that he smokes, but to materialize a distance from the world. James Dean, in Rebel Without a Cause (1955), holds his cigarette as an act of defiance. It becomes the symbol of a youth in rupture, misunderstood and unstable.

These figures are not accidental. They belong to a well identified cinematic tradition in which the cigarette becomes a genuine tool of characterization. In film noir and postwar American cinema, smoking is part of the visual grammar: a scripted, staged, and repeated gesture that defines a character instantly.

The result is clear. By consistently associating cigarettes with strong, desirable, or morally complex characters, cinema helped place smoking at the center of the collective imagination. On screen, smoking is not a neutral behavior. It is a sign, a posture, sometimes even a promise. Repeated film after film, this symbolic charge ultimately produces real effects on viewers.

The repeated faces of the cinematic smoker

Over the decades, Hollywood cinema did not simply show characters who smoke. It stabilized recurring figures that are immediately recognizable, in which the cigarette plays a precise role. These archetypes function because they are readable, repeated, and deeply embedded in visual storytelling.

The rebel smoking as an act of rupture

The most iconic example remains James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause (1955). His cigarette is neither elegant nor discreet. It is held nervously, sometimes awkwardly, as an extension of his inner discomfort. Here, smoking does not signify pleasure but transgression. The gesture signals opposition to rules, authority figures, and social order. This type of representation is central. The cigarette becomes a marker of independence, even refusal. For the viewer, particularly younger audiences, it acquires strong symbolic value associated with emancipation.

This link between on screen smoking and transgressive figures is not merely a critical intuition. It is documented. A content analysis conducted by the United States National Cancer Institute on popular Hollywood films released between 1950 and 2006 shows that the 1950s marked the historical peak of tobacco representation on screen, with a strong concentration among central characters portrayed as independent, nonconformist, or in conflict with authority. Source National Cancer Institute Monograph No. 19 The Role of the Media in Promoting and Reducing Tobacco Use 2008.

🔗Read also: The book of laughter and forgetting: A fight against erasure

The seducer or seductress a cigarette named desire

Lauren Bacall in To Have and Have Not (1944) perfectly embodies this archetype. Her way of smoking is slow, controlled, almost choreographed. The cigarette becomes a tool of tension and desire. It structures silences, prolongs glances, and occupies the space between characters. In this register, the cigarette belongs to an aesthetic of control and sophistication. It expresses not lack, but self mastery.

This staging is not incidental. A detailed analysis of classic Hollywood films conducted by the National Cancer Institute shows that stars, both men and women, are very frequently associated with cigarettes in scenes of seduction, control, and symbolic power, contributing to the lasting anchoring of tobacco in the cinematic imagination of glamour. Source Tobacco Control Monograph No. 19 2008.

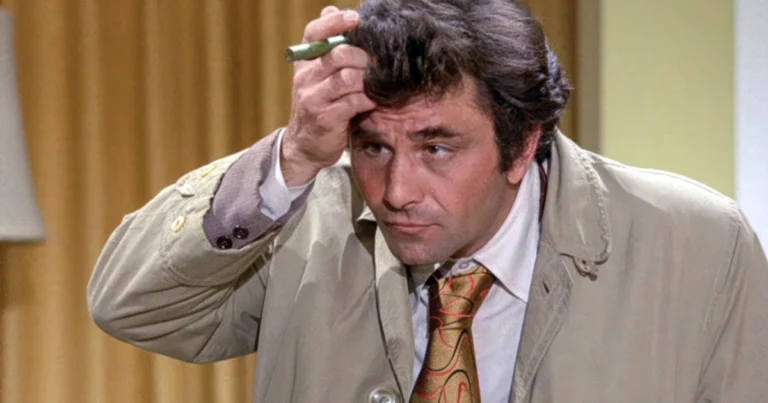

The tormented intellectual i think therefore i smoke

In film noir and its successors, the cigarette often accompanies characters assumed to think more than they act. Humphrey Bogart again, in The Big Sleep (1946), smokes while investigating, waiting, and doubting. Smoke becomes a visible metaphor for thought itself, opaque, drifting, never fully clear.

This type of representation associates smoking with introspection, mental fatigue, and the weight of reality. It suggests psychological depth without verbal exposition. For the viewer, the implicit message is powerful. Smoking becomes a sign of intelligence, lucidity, sometimes disenchanted lucidity.

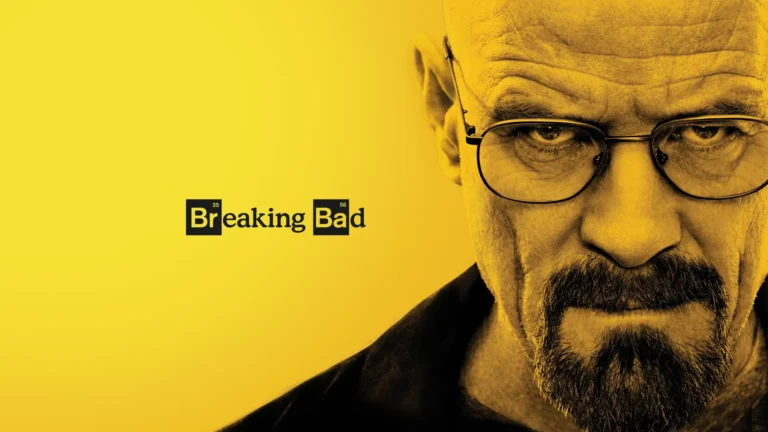

The modern antihero the cigarette as a flaw

In more contemporary cinema, the cigarette no longer openly glorifies. It humanizes. A striking example is Vincent Vega, played by John Travolta in Pulp Fiction (1994). He often smokes during moments of hesitation, waiting, or absurd tension. The cigarette does not make him stronger or more attractive. It highlights his imperfection.

This archetype matters because it reflects an evolution. The cigarette is no longer a symbol of domination but an indicator of vulnerability. Nevertheless, it remains associated with charismatic, memorable characters to whom viewers become attached. Identification persists even as meaning shifts.

What ultimately links these characters is their central place in the narrative. They are the ones we follow, whose silences, flaws, and gestures we remember. They leave a strong emotional imprint and consistently radiate charisma, complexity, and shadow.

The cigarette then acts as a symbolic shortcut. It condenses identity into a single gesture. Because these figures repeat across eras and genres, viewers unconsciously learn to associate this gesture with valued human qualities. This repetitive, implicit, emotional mechanism is precisely what public health research identifies as a determinant of tobacco’s durable anchoring in the collective imagination.

Why do we identify with smokers

Cinema’s influence does not operate through conscious reasoning. No one leaves a theater thinking they want to smoke because a character did so on screen. The mechanism is far more discreet and far more powerful.

In psychology, this phenomenon is known as social learning, a theoretical model developed by Albert Bandura and extensively validated. The principle is simple. We internalize behaviors by observing those we perceive as legitimate, admirable, or emotionally close. The more charismatic and narratively central a character is, the more their behavior becomes an implicit reference.

Public health studies rely on this framework to analyze the impact of on screen smoking. A study cited on Cairn.info shows that high exposure to films depicting smokers multiplies by 2.6 the risk of smoking initiation among adolescents aged ten to fourteen, confirming that identification mechanisms have measurable effects, particularly among younger viewers. The conclusion is clear. When valued characters smoke repeatedly without visible negative consequences, the brain records the association as normal, even coherent with a certain identity.

For this reason, the United States Surgeon General, the official authority in American public health, concluded that there is a causal relationship between exposure to smoking scenes in films and smoking initiation among youth. Not because cinema directly encourages smoking, but because it embeds the gesture within human trajectories with which viewers identify. The cigarette does not impose itself as a product. It imposes itself as a behavior that makes sense within a story. It is this narrative logic, repeated film after film, that leaves a lasting trace.

🔗Explore further: Dostoevsky through Freud’s eyes

The cult scene emotion told through a cigarette

Certain scenes remain etched long after the credits roll. We remember a glance, a silence, a wait. And very often, a cigarette. On screen, cigarettes rarely appear in moments of pure action. They emerge in suspended moments, just before a decision, after a shock, during endless waiting. They mark a pause, a narrative breath. The story slows, emotion surfaces, and attention sharpens.

This is where the mechanism operates. The cigarette becomes a visual anchor within an emotionally charged scene. It accompanies romantic tension, existential doubt, or deep loneliness. The brain does not memorize only the scene. It memorizes the entire tableau, atmosphere, character, and gesture together.

In many cult films, the cigarette is not overtly central, but it is inseparable from the memory of the scene. It structures rhythm, gives tempo to silence, occupies hands when words fail. It becomes an instrument of emotional staging. Neuroscience of memory shows that emotionally salient moments are encoded most durably. Without ever being the main subject, the cigarette becomes associated with intense states such as desire, melancholy, tension, and lucidity.

Through repetition, film after film, this link becomes automatic. The cigarette is no longer perceived as external to the scene but as a natural element of the emotional landscape. It belongs to these moments. This silent, nearly invisible integration is precisely what makes it so powerful in the spectator’s imagination.

From normalization to lasting anchoring why these images endure

What is most striking is not that cinema creates associations. It is that they persist. Even when the dangers of tobacco are known, documented, and socially integrated, certain images continue to exert influence. The reason lies in how the brain prioritizes memory. Rational knowledge, statistics, risks, and warnings rely on conscious cognitive systems accessible in the short term. Emotional images are encoded in older, deeper systems less accessible to logical reasoning.

When cigarettes are associated on screen with pivotal moments such as solitude, desire, lucidity, or tension, they bind to universal internal states. The brain immediately recognizes these states because they are part of human experience. What is linked to them consolidates durably. This explains why prevention messages, however necessary, sometimes struggle to fully neutralize the impact of cultural imagery. They do not operate at the same level. Prevention speaks to reasoning. Cinema acts on affective memory.

Over time, this gap explains why certain representations persist in the collective imagination even when their danger is socially acknowledged. The cigarette is no longer perceived as a rational choice but as an inherited symbol rooted in older images.

Today, cinema’s role can no longer be considered as it was in the mid twentieth century. Images circulate more widely and embed themselves more deeply into daily life through platforms and serialized viewing. In this context, the question is no longer solely artistic freedom, but cultural responsibility.

🔗 Discover more: The Psychologist on screen: From savior to shadow

For decades, cinema contributed, sometimes consciously and often through inheritance, to installing the cigarette as a narratively charged sign. Even when tobacco is no longer portrayed as desirable, its mere presence continues to activate older associations forged through years of repetition. Ignoring this legacy underestimates the cumulative power of images.

Contemporary cinema is not static. Some works attempt to dismantle these mechanisms by showing smoking without glamour, within contexts of dependence, fatigue, or loss of control. Others link the gesture to visible consequences rather than seduction or lucidity. Some choose to abandon it entirely, refusing to use the cigarette as a symbolic shortcut.

These approaches do not moralize. They shift perspective. They remind us that images are never neutral and that human complexity can be portrayed without relying on inherited symbols whose impact extends far beyond fiction. Ultimately, the question is not whether to censor the past or erase cigarettes from screens. It is what cinema chooses to transmit today and which associations it continues, consciously or not, to anchor in collective memory.

References

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Dalton, M. A., Sargent, J. D., Beach, M. L., Titus-Ernstoff, L., Gibson, J. J., Ahrens, M. B., & Heatherton, T. F. (2003). Effect of viewing smoking in movies on adolescent smoking initiation: A cohort study. British Medical Journal, 326(7380), 1–6.

National Cancer Institute. (2008). The role of the media in promoting and reducing tobacco use (Tobacco Control Monograph No. 19). Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2012). Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

World Health Organization. (2016). Smoke-free movies: From evidence to action (2nd ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization.

Amine Lahhab

Television Director

Master’s Degree in Directing, École Supérieure de l’Audiovisuel (ESAV), University of Toulouse

Bachelor’s Degree in History, Hassan II University, Casablanca

DEUG in Philosophy, Hassan II University, Casablanca