Parkinson’s disease: When automatic movement breaks down

Parkinson’s disease is often reduced, in the public imagination, to one striking image: a trembling hand. While memorable, that picture is profoundly incomplete. It obscures the reality of a complex, progressive neurological disorder that reaches far beyond tremor and gradually reshapes the person’s entire psychocorporeal functioning.

Parkinson’s disease affects the brain’s motor circuits, but also networks involved in regulating muscle tone, rhythm, attention, and emotion. It disrupts movement in its fluidity, spontaneity, and automaticity, making every action more effortful, slower, and sometimes hesitant. A body that once felt self-evident and silent becomes constrained, stiff, unpredictable, and increasingly dependent on constant voluntary control.

Parkinson’s does not unfold solely in the motor domain. It also alters the internal sense of rhythm, the rhythm of walking, gesturing, and speaking, as well as the ability to adjust to time and space. Attention becomes more fragile. Initiating an action, anticipating a movement, and shifting smoothly from one gesture to another can all become difficult. Emotionally, anxiety, apathy, or depression often intensify motor challenges, creating a vicious cycle in which psychic inhibition and bodily inhibition reinforce one another. Over time, the relationship to the world itself changes. Walking outside, stepping through a doorway, rising from a chair, or writing can become sources of apprehension. Movement is no longer spontaneous; it is planned, monitored, and sometimes feared. The body stops being a natural support for action and becomes an object of constant vigilance.

This is precisely where psychomotor therapy becomes especially relevant: at the crossroads of neurological, bodily, motor, cognitive, and emotional processes. As a discipline grounded in the connection between mind and movement, it invites us to understand Parkinson’s not only as a motor disorder, but as a global disruption of lived bodily experience. A psychomotor perspective focuses not simply on what no longer works, but on how the person feels their body, engages in action, adapts to difficulties, and strives to preserve psychocorporeal balance in everyday life.

Understanding Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease is a chronic, progressive neurological condition caused by the gradual dysfunction of deep brain circuits involved in movement control. It is primarily linked to the degeneration of neurons in a structure called the substantia nigra, a small region in the brainstem that plays a central role in motor regulation. These neurons have a crucial function: producing dopamine, a neurotransmitter essential for efficient transmission of motor information between different brain regions.

Dopamine acts as a genuine modulator of movement. It helps the brain select, initiate, and coordinate actions in a way that is fluid and appropriate to the situation. As dopamine production progressively declines, as it does in Parkinson’s disease, the balance within motor circuits is disrupted. The brain then struggles to trigger movement, adjust its intensity, and maintain continuity. Gestures that were once automatic become slow, fragmented, and costly in terms of attentional effort.

In practical terms, this dopaminergic decline undermines the brain’s ability to initiate movement spontaneously. The transition from intention to action becomes more laborious, leading to a generalized slowing of movement. Motor fluidity is also affected: movements lose their suppleness, become jerky or reduced, with diminished amplitude and speed. The mechanisms of automaticity that normally allow us to act without conscious effort begin to break down. Everyday actions such as walking, standing up, writing, or fastening buttons may then require sustained, conscious attention.

From a motor standpoint, these neurological disruptions produce a characteristic set of signs. Bradykinesia, the slowness of movement, is the core symptom of the disease. It is often accompanied by muscular rigidity, linked to an abnormal increase in muscle tone, which limits ease of movement and can contribute to pain. Resting tremor, though widely publicized, is neither constant nor universal and may be absent in some patients. Balance and postural difficulties can also develop, leading to increasing instability and a higher risk of falls.

However, limiting Parkinson’s disease to these motor manifestations gives an incomplete picture. The same brain circuits involved in movement control also contribute to regulating attention, emotion, and behavior. Parkinson’s is therefore not merely a disorder of movement; it affects the person’s entire neuropsychomotor functioning, opening the way to a broader and more humane understanding of this condition.

🔗Read also: Two disorders, one trajectory? Rethinking the divide between autism and Parkinson’s

When the body feels different: Lived experience in Parkinson’s

Beyond visible, measurable motor symptoms, Parkinson’s disease profoundly transforms the relationship a person has with their own body. A body that once felt reliable, quiet, and naturally available for action can gradually become unpredictable, constraining, and at times strangely unfamiliar. This shift in lived bodily experience is central to the illness. It is often difficult to put into words, yet it permeates daily life.

Many people with Parkinson’s describe a body that no longer responds as it used to. Gestures no longer arise spontaneously; they must be thought through, prepared, and controlled. This loss of bodily self-evidence is frequently accompanied by sensations of heaviness, stiffness, or blockage, as if the body were resisting movement. Some patients speak of feeling “frozen,” “held back,” or “slowed from the inside,” conveying the difficulty of engaging in action despite the desire to move.

Gestural spontaneity is also diminished. Movements become smaller, less expansive, less expressive. The face may appear less animated, gestures can lose their natural quality, and walking may become shorter and more rigid. This reduction in bodily expressiveness directly affects nonverbal communication and relationships with others, sometimes intensifying feelings of isolation or being misunderstood. Fatigue often compounds the situation, both motor and mental, driven by the continuous effort required to control each action and compensate for failing automatisms.

Alongside motor symptoms, Parkinson’s disease very often involves so-called non-motor symptoms that contribute significantly to altered bodily experience. Difficulties in attention and planning can make organizing gestures and daily activities more complex. Anxiety, apathy, or depressive episodes can directly reduce psychological readiness for movement, worsening slowness and blockages. Sleep disturbances heighten fatigue and weaken adaptive capacities. Finally, changes in body perception may emerge, affecting how a person senses their body, their support on the ground, their balance, or the position of their limbs in space.

At this level, a neuropsychomotor perspective becomes fundamental. It reminds us that movement is never a purely mechanical output; it is the product of a continuous interaction between the body, the mind, emotion, and cognition. In Parkinson’s disease, these dimensions are tightly intertwined. A motor difficulty may be intensified by anxiety. An attentional disturbance may impair movement initiation. An altered body schema may disrupt coordination. Psychomotor therapy therefore offers an integrative reading of Parkinson’s, centered on lived bodily experience and on the ways a person, day after day, continues to inhabit their body despite the illness.

When movement stops being automatic

In Parkinson’s disease, one of the most destabilizing changes is the loss of automaticity. Actions that once required no conscious effort, walking, rising from a chair, turning around, writing, reaching for an object, can suddenly become complex tasks that demand sustained attention and mental preparation. Movement no longer emerges naturally; it must be planned, anticipated, and sometimes broken down into successive steps.

This loss of automaticity forces the person to recruit significant cognitive resources to compensate for disrupted motor circuits. What used to be fluid and integrated becomes controlled, deliberate, and often rigid. The person must quite literally “think the movement,” turning everyday actions into mentally expensive and exhausting situations. This constant attentional mobilization leaves little room for spontaneity and greatly increases cognitive load.

That overload has direct consequences for motor function. It can trigger sudden motor blocks known as freezing episodes, during which a person becomes briefly unable to start or continue a movement, especially while walking or changing direction. These episodes are unpredictable and destabilizing, deepening the sense of losing control over one’s own body. Marked fatigability also develops, both physical and psychological, stemming from the continuous effort required to maintain action and stay focused on the gesture.

Over time, repeated experiences of failure or blockage can erode confidence in one’s motor abilities. The person begins to anticipate difficulty before acting, fearing movement, unfamiliar situations, or complex environments. Anticipatory anxiety may then take hold, worsening motor symptoms and reinforcing the vicious cycle between emotional tension, cognitive inhibition, and bodily freezing.

A neuropsychomotor approach helps make sense of these difficulties by understanding them as the result of disrupted coordination between several fundamental dimensions. A motor system weakened by dopamine deficiency can no longer ensure fluid action on its own. Cognitive functions, particularly attention, planning, and executive control, become overused as compensatory mechanisms. A less stable body schema disrupts perception of the moving body and postural adjustment. Finally, altered tonic emotional regulation, shaped by anxiety and muscular rigidity, interferes with gesture quality. Neuropsychomotor therapy thus provides an integrative understanding of Parkinson’s disease, highlighting the constant interdependence between movement, cognition, emotion, and lived bodily experience.

🔗Explore further: When Alzheimer’s disrupts the body’s inner map

Psychomotor therapy: A global and deeply human approach

Psychomotor therapy is not limited to motor rehabilitation in the narrow sense. It does not aim solely to correct a faulty gesture or normalize performance. Its primary focus is to understand and support how a person lives in their body day by day. It explores how an individual inhabits their body, senses their actions, anticipates movement, and locates themselves in space and time. This global approach considers movement as an experience that is bodily, psychological, and relational all at once.

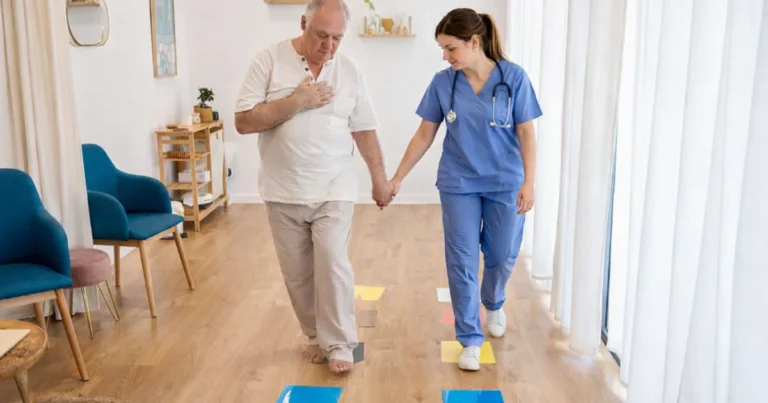

For someone living with Parkinson’s disease, psychomotor work is guided by the goal of re-harmonizing psychocorporeal functioning. The psychomotor therapist supports motor fluidity by helping the person recover movement sequences that are more supple and less costly. Global and fine coordination are addressed to facilitate everyday gestures, whether walking, transfers, manual activities, or writing. Balance and posture are central as well, with the aim of strengthening stability, improving adaptive reactions, and making mobility safer.

Regulation of muscle tone is another major focus. In Parkinson’s disease, tone often becomes excessive, rigid, and poorly adaptable, limiting mobility and amplifying fatigue. Psychomotor therapy works to restore more flexible tonic modulation through alternating phases of mobilization, release, and bodily awareness. Rhythm, often deeply disrupted, is also at the heart of this support. Whether the rhythm of walking, gesturing, or breathing, the therapist helps the person rebuild stable and reassuring temporal anchors that make engagement in action easier.

Beyond these motor dimensions, psychomotor therapy fully engages with subtler aspects of psychological functioning. Work on attention helps sustain the concentration necessary for action without exhausting cognitive resources. Emotional regulation is essential to reduce the impact of anxiety, stress, or fear of movement, which frequently intensify motor blockages. Body image, often shaken by the illness, is addressed to help the person reclaim a body that may feel unreliable or unfamiliar.

Psychomotor therapy also gives a fundamental place to the pleasure of moving, even in new ways. Restoring a positive, playful, and valuing relationship to movement breaks with a purely deficit-based view of the body. Through adapted, safe, and meaningful movement situations, the psychomotor therapist supports the person with Parkinson’s in a process of bodily re-engagement, strengthening autonomy, self-confidence, and quality of life.

Restoring meaning to movement

Psychomotor rehabilitation for Parkinson’s disease is grounded in functional and psychocorporeal readaptation, not in the pursuit of performance or a return to “normal” movement. The goal is not to do more or do better, but to do differently, taking into account the person’s current capacities, the course of the disease, and their lived bodily experience. This respectful approach aims to preserve autonomy, secure everyday actions, and maintain a satisfying quality of life.

Care often includes gentle mobilization exercises to counteract muscular stiffness and promote bodily availability. These mobilizations, adapted to the person’s pace, help maintain range of motion and limit the loss of flexibility. Rhythm and coordination activities are also important, because rhythm can serve as a crucial support for initiating and chaining movements. Using playful and structured cues, the person is guided toward stable temporal markers that support action.

The proposed movement situations are designed to be meaningful and functional, directly connected to daily gestures. Movement is never detached from its context. It is embedded in an action that matters to the person, which strengthens engagement and motivation. Work on breathing and relaxation helps reduce tonic rigidity and soothe the emotional tensions frequently associated with the disease. Sensory and proprioceptive stimulation strengthens bodily perception, improves postural adjustments, and supports awareness of the moving body.

Within this framework, the psychomotor therapist helps the person learn practical strategies to cope with motor difficulties. This includes approaches to bypass blockages, such as using movement “starters,” changing rhythm, or modifying the environment. Visual, auditory, or bodily cues can facilitate movement initiation and reduce cognitive overload. Over time, the person builds effective strategies that can be transferred into daily life, strengthening their sense of competence and autonomy.

Each psychomotor session is conceived as a safe, containing, and supportive space. It is a place where the body can dare to move again, explore, make mistakes, and succeed, without fear of being judged or failing. In that space, movement regains its status as lived experience, allowing the person with Parkinson’s to reclaim their body and, as much as possible, reconnect with the simple satisfaction of acting.

🔗Read also: From loss to repair: Stem cells offer new hope for Parkinson’s

A complementary and essential contribution

Psychomotor therapy offers a complementary and essential contribution to Parkinson’s care, without replacing medication or other rehabilitation approaches. Pharmacological treatments, particularly those that compensate for dopaminergic deficiency, remain crucial for improving motor symptoms. The interventions of other health professionals are equally important, each addressing specific and complementary goals. Psychomotor therapy naturally belongs within this collaborative, coordinated model of care.

Within a multidisciplinary approach, the psychomotor therapist works closely with the neurologist, physiotherapist, speech and language therapist, and neuropsychologist. The neurologist ensures diagnosis, medical follow-up, and treatment adjustments. The physiotherapist focuses more specifically on muscle strengthening, joint mobility, and fall prevention. The speech and language therapist addresses difficulties in speech, voice, and swallowing. The neuropsychologist assesses and supports cognitive and executive functions. Psychomotor therapy complements these perspectives by providing a cross-cutting understanding of psychocorporeal functioning.

The specificity of psychomotor therapy lies in its ability to link brain and body while acknowledging the constant interplay between neurological mechanisms and bodily expression. It also bridges movement and emotion, recognizing how affective states and motor quality mutually influence one another. Anxiety, fear of freezing, or loss of confidence can worsen motor symptoms, while better emotional regulation can facilitate engagement in action. Psychomotor therapy also connects motor function with subjective experience by attending to how the person perceives, feels, and invests their body in daily life.

Through this integrative perspective, psychomotor therapy helps bring coherence to care. It moves beyond a strictly symptom-based view and supports the person across all dimensions of bodily experience. By working at the interface of the somatic and the psychological, it actively contributes to preserving autonomy, bodily identity, and quality of life for people living with Parkinson’s disease.

Ultimately, Parkinson’s disease is commonly described as a disorder of movement, but that definition alone does not do justice to the lived reality of those affected. Beyond visible motor symptoms, the entire relationship to the body is profoundly transformed. Gestures lose their self-evidence. The body becomes a source of doubt, fatigue, and at times suffering. Daily life is shaped by constant adjustments. Parkinson’s is therefore also a disorder of the lived body, in which movement, emotion, cognition, and bodily identity are tightly intertwined.

In this context, psychomotor therapy offers a distinctive response that is global, sensitive, and deeply human. It is not limited to functional retraining; it supports the person in finding ways to inhabit their body despite the illness. By taking subjective experience, psychological resources, and remaining motor capacities into account, it helps the person remain an agent of their body rather than a mere spectator of limitations.

Restoring meaning to gesture means helping the person understand, adjust, and reinvest movement in concrete, meaningful situations. Rebuilding confidence means allowing the body to move without the constant fear of failure or the gaze of others. Preserving dignity means recognizing the person as a whole, beyond symptoms. Maintaining the pleasure of moving, even differently, supports vitality and quality of life in the face of a progressive illness.

Faced with Parkinson’s disease, psychomotor therapy does not seek to fight the body, but to work with it. It supports the person through continuous adaptation, so that movement can remain possible, meaningful, and human, even in the presence of the disease.

References

Poewe, W., Seppi, K., Tanner, C. M., Halliday, G. M., Brundin, P., Volkmann, J., Schrag, A.-E., & Lang, A. E. (2017). Parkinson disease. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 3, 17013.

Bloem, B. R., Okun, M. S., & Klein, C. (2021). Parkinson’s disease. The Lancet, 397(10291), 2284–2303.

Saad Chraibi

Psychomotor Therapist

• A graduate of Mohammed VI University in Casablanca, currently practicing independently in a private clinic based in Casablanca, Morocco.

• Embraces a holistic and integrative approach that addresses the physical, psychological, emotional, and relational dimensions of each individual.

• Former medical student with four years of training, bringing a solid biomedical background and clinical rigor to his psychomotor practice.

• Holds diverse professional experience across associative organizations and private practice, with extensive interdisciplinary collaboration involving speech therapists, psychologists, neuropsychologists, and other healthcare professionals.

• Specializes in tailoring therapeutic interventions to a wide range of profiles, with a strong focus on network-based, collaborative care.

• Deeply committed to developing personalized therapeutic plans grounded in thorough assessments, respecting each patient’s unique history, pace, and potential, across all age groups.