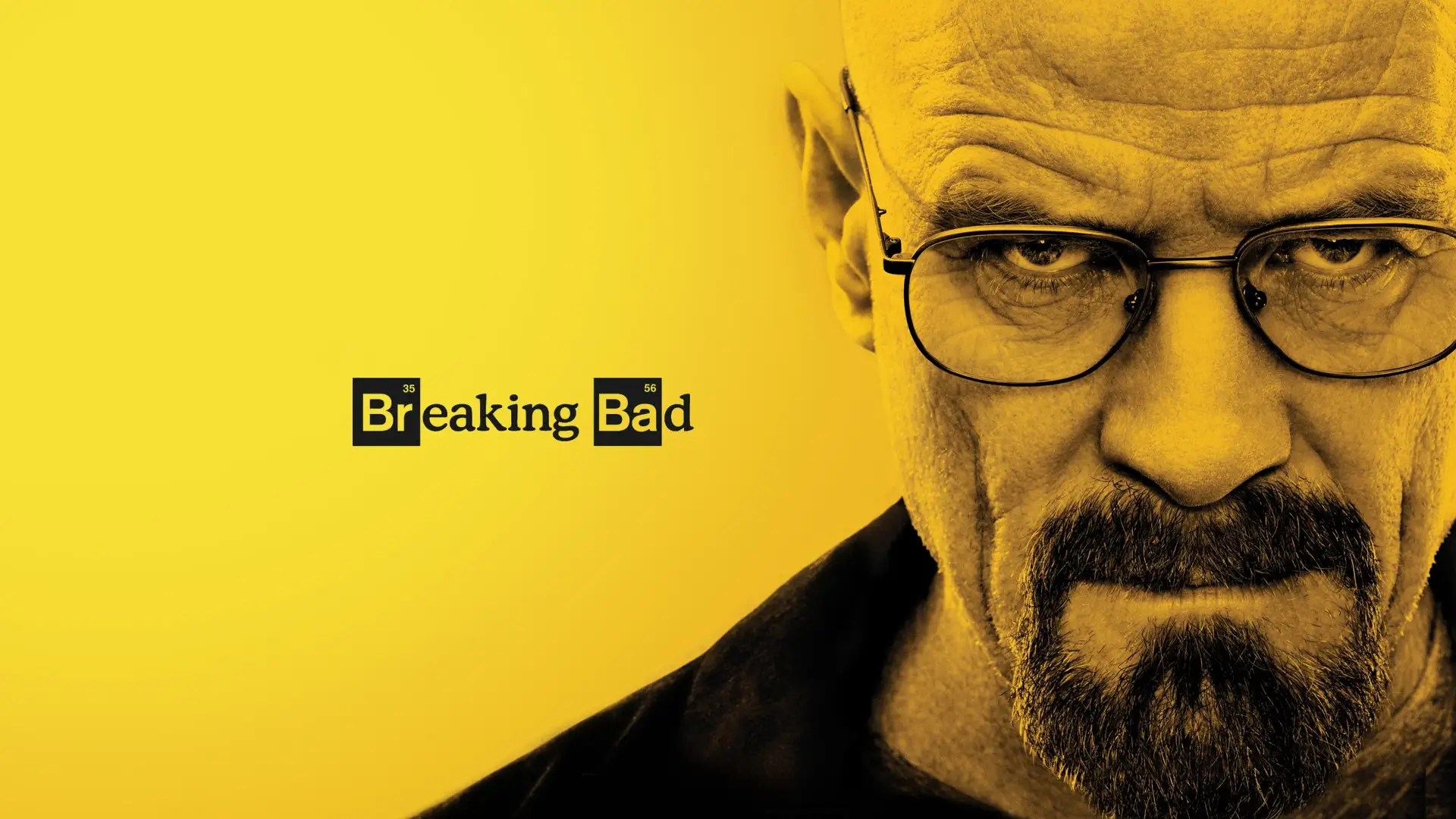

Breaking Bad how fiction trains us to follow evil

I’m not in danger, Skyler. I am the danger.

Yes, we loved this series. Yes, it regularly appears at the top of global rankings. And yes, I personally followed Walter White with fascination, episode after episode. However, is it not unsettling, almost unhealthy, to idolize a teacher turned criminal, a power hungry drug trafficker willing to kill to climb the hierarchy of organized crime?

This tension lies at the heart of Breaking Bad. How can a work of fiction captivate us so deeply, attach us emotionally, and sometimes even lead us to hope for Walter White’s success, when his actions would place him, outside fiction, firmly among those we condemn without hesitation?

Broadcast from 2008 to 2013, the series did more than gather millions of viewers around a dark narrative. It became a global cultural phenomenon. Walter White, also known as Heisenberg, transcended the television screen to embed himself in popular culture. His face, his cold gaze, and several of his lines “I am the danger” or “Say my name” have been repeated, translated, and memorized by fans, becoming almost mythological lines of twenty first century television.

The imagery and symbols of the series also entered the real world. T shirts bearing the logo of Los Pollos Hermanos, the fictional restaurant used as a criminal front in the series, are worn by fans and sold in specialized shops. A fictional symbol has become an instantly recognizable fashion item. This attachment goes beyond simple costume play. It reflects a deep resonance between the audience and the series’ narrative aesthetic, where fictional elements become markers of cultural identity.

Seeing through Walter White’s eyes

From the very beginning, Breaking Bad adopts a precise narrative strategy. It aligns the viewer with Walter White. The series chooses to move forward with him, rarely against him. We know what he knows. We discover events at his pace. We are placed inside the continuity of his decisions. Before any moral evaluation, the series imposes a point of view.

In film theory, this mechanism is often described as spectator alignment, a concept notably developed by Murray Smith. This is not yet moral empathy or ethical endorsement, but a sharing of information, perception, and perspective. The viewer is not invited to approve of Walter White, but to understand his reasoning from the inside.

A scene from the very first episode illustrates this perfectly. During the ride along with Hank Schrader, Walter accompanies his brother in law on a drug enforcement operation. The sequence is decisive. The viewer observes the world of methamphetamine trafficking not through the eyes of law enforcement, but through Walter’s gaze. The camera lingers on what he sees: seized money, the apparent ease with which others exploit chemical knowledge he masters better than they do, and above all the silent humiliation of feeling invisible, useless, underestimated. Nothing illegal has happened on his side yet, but narratively, everything is already in place.

At this moment, the series does not show us the consequences of crime. It shows perceived injustice, imbalance, the gap between competence and recognition. The viewer does not follow an ideology. The viewer follows a line of reasoning. And because we share Walter White’s information and perspective, critical distance begins to shrink, often without our full awareness.

This narrative choice is fundamental. It prepares the ground for everything that follows. By placing us so early inside Walter White’s perspective, Breaking Bad enables a gradual shift. We are not yet empathizing, but we have already left neutrality. And once this shift occurs, judgment becomes more difficult.

🔗Read also: The Psychologist on screen: From savior to shadow

How small choices redefine morality

If Breaking Bad succeeds in making us accept the unacceptable, it does so not through abrupt rupture, but through gradual drift. The series exploits a well documented psychological mechanism. We tolerate transgression more easily when it is incremental and initially framed as serving a seemingly legitimate cause, such as protecting one’s family, ensuring financial survival, or correcting perceived social injustice.

In moral psychology, this phenomenon is linked to what some researchers describe as the progressive normalization of deviance. A first morally questionable action, when it appears understandable, becomes an anchor point. Subsequent actions, even more severe, are then evaluated not against an external moral standard, but in comparison to previous choices. The threshold of tolerance shifts.

Breaking Bad follows this logic precisely. Walter White never crosses the line all at once. Each step is presented as a contextual response, almost reasonable within its immediate circumstances. The narrative does not ask the viewer to accept crime as a whole, but to accept each decision in isolation. It is this moral fragmentation that makes the whole bearable, at least for a time.

When evil is well crafted

If Breaking Bad renders Walter White fascinating, it is not only through writing or narrative progression, but through an exceptionally deliberate visual language. The series does not simply tell the story of his rise to power. It stages it, stylizes it, and makes it visually desirable.

As the seasons progress, the direction mirrors Walter White’s transformation into a figure of power. The visual grammar evolves with him. As Walter asserts authority, the camera increasingly frames him as dominant, using low angle shots, stable compositions, symmetry, and central positioning. Where early Walter is often overwhelmed by his environment, lost in wide frames and dominated by others, Heisenberg gradually occupies space. The image belongs to him.

The series also cultivates an aesthetic of control and mastery. Many scenes show Walter remaining still while the world around him moves. Silences are extended. Dialogue is reduced. Threat is suggested rather than spoken. This restraint enhances the impression of power. Walter no longer needs to persuade. He imposes. The viewer is invited to admire this visual transformation, often unconsciously.

Violence is treated with similar care. Breaking Bad does not always depict it directly. It is often prepared, ritualized, followed by moments of almost aesthetic calm. Certain deaths or acts of domination are filmed with formal precision that partially neutralizes their moral brutality. Violence becomes a strong narrative event, almost beautiful in its construction. This does not excuse the acts, but it alters their emotional reception.

Music plays an equally central role. Rather than emphasizing moral gravity, it often accompanies Walter’s moments of success with ironic, stylized, or energetic choices. These sequences transform criminal acts into moments of narrative triumph. The viewer experiences aesthetic satisfaction that conflicts with the moral content of the scene.

Finally, the series’ overall aesthetic, contrasting colors, symbolic costumes, iconic settings, builds a visual mythology. Heisenberg’s black hat, the underground lab, the New Mexico desert. These elements contribute to Walter White’s iconization. He becomes not just an individual, but a figure. And in cinema, figures invite contemplation more readily than rejection.

Here is where glorification fully operates. Breaking Bad never explicitly tells us to admire Walter White. It does so indirectly, by filming him as cinema traditionally films powerful, charismatic, memorable characters. Evil is not justified through discourse. It is embellished through form. And when form seduces, moral judgment recedes.

🔗Explore further: Falling down: when one man’s collapse mirrors a society in crisis

I Did It for Me I Liked It I Was Good at It I Was Alive

When Walter White shaves his head, something closes. His face becomes harder, more legible, almost iconic. He is not yet Heisenberg at full power, but he is no longer the ordinary man he claims to be. From this point on, he no longer seeks to be judged or understood. The question is no longer good versus evil in a collective sense, but a personal morality constructed by his own rules.

At this stage, Breaking Bad performs a decisive shift. The series no longer asks the viewer to evaluate Walter’s actions according to shared moral standards, but to assess their internal coherence. Moral judgment is replaced by logical consistency. The implicit question becomes not “Is this right?” but “Is this consistent with who he has become?”

This process is central. The series does not push us to approve of Walter White. It trains us to follow his logic. Each decision is framed as a rational step within an already established system. Acts are no longer isolated, but integrated into a narrative continuity that gives them functional meaning. The viewer stops evaluating human consequences and instead evaluates the strength of the reasoning.

Walter’s morality becomes a narrative tool. It filters the viewer’s perception. As long as this internal morality remains stable, structured, intelligible, cognitive adherence is maintained. The viewer may disapprove abstractly, yet continue to follow, anticipate, and wait for the next move like a chess match.

This shift is reinforced by the series’ avoidance of direct moral confrontation. Ethical consequences are often delayed, displaced, or absorbed by narrative logic. Suffering exists, but rarely occupies center stage. What prevails is the coherence of the system Walter has built, a system that functions, at least temporarily.

Thus, Breaking Bad does not erase morality by denying it, but by relocating it. A collective morality based on shared rules is replaced by a functional morality based on efficiency and coherence. As long as that coherence holds, the viewer holds with it.

This is where the series becomes most disturbing. It shows that evil does not need to be seductive to be accepted. It only needs to be logically narrated.

🔗Read also: The hidden language of smoking in cinema

The trap of narrative empathy

The moral drift is now firmly established. Identification with Walter White has taken place. Breaking Bad goes further by placing the viewer in a position of involuntary emotional complicity. Certain scenes are designed to generate tension and even relief when Walter escapes immediate consequences. This relief is revealing. It does not indicate conscious moral approval, but it exposes an affective involvement patiently constructed by the series.

This is where Breaking Bad becomes profoundly unsettling. It never explicitly asks us to love Walter White. It demonstrates instead that under certain narrative conditions, we can continue to feel empathy for a character we rationally condemn.

Through form, logic, and continuity of perspective, Breaking Bad does not merely represent evil. It organizes its glorification by gradually weakening the viewer’s moral judgment.

In this sense, Breaking Bad does not only tell the story of a man’s downfall. It reveals a vulnerability within the viewer. It shows that empathy, far from being a reliable moral compass, can become a narrative reflex. And once that reflex is established, evil no longer needs justification or defense. It is simply followed, unless the viewer consciously chooses to restore critical distance.

This fascination did not remain confined to the screen. In 2015, in Italy, a twenty two year old student was arrested following the dismantling of a clandestine methamphetamine laboratory. Authorities explicitly stated that the young man had been inspired by Breaking Bad and by Walter White, the chemistry teacher turned drug manufacturer. This is not about accusing fiction of causing crime, but about recognizing how deeply narrative can shape imaginaries, models, and desires for transgression.

This case acts as a revealing signal. Breaking Bad does not push viewers to manufacture drugs. It shows that a story can make evil intelligible, fascinating, and potentially imitable.

References

Bandura, A. (2016). Moral disengagement: How people do harm and live with themselves. Worth Publishers.

Bordwell, D. (1985). Narration in the fiction film. University of Wisconsin Press.

Elsaesser, T., & Hagener, M. (2015). Film theory: An introduction through the senses. Routledge.

Mittell, J. (2015). Complex TV: The poetics of contemporary television storytelling. New York University Press.

Plantinga, C. (2018). Screen stories: Emotion and the ethics of engagement. Oxford University Press.

Prince, S. (2003). Classical film violence: Designing and regulating brutality in Hollywood cinema. Rutgers University Press.

Smith, M. (1995). Engaging characters: Fiction, emotion, and the cinema. Oxford University Press.

Amine Lahhab

Television Director

Master’s Degree in Directing, École Supérieure de l’Audiovisuel (ESAV), University of Toulouse

Bachelor’s Degree in History, Hassan II University, Casablanca

DEUG in Philosophy, Hassan II University, Casablanca