Bīmāristāns: When medicine and compassion transformed history

The common perception of medieval hospitals is often bleak, unsanitary places offering only rudimentary care. However, this view, largely shaped by misconceptions, overlooks a far more nuanced reality, particularly within the Muslim world. Contrary to simplistic portrayals of the Middle Ages, Islamic civilization experienced an era of remarkable medical advancements, embodied by the Bīmāristāns, sophisticated and innovative institutions that redefine our understanding of healthcare in that period. Far from being mere shelters for the sick, these establishments, whose name literally means “place of care”, were comprehensive medical centers, true beacons of research and clinical practice. Their emergence marked a major turning point in the history of medicine, with lasting implications for future medical practices.

From faith to science: the birth of islamic medical institutions

The development of Bīmāristāns in medieval Islamic civilization cannot be understood without considering its unique historical and religious context. The rapid expansion of Islam from the 7th century onward facilitated an extensive network of cultural and scientific exchanges, bringing together and preserving medical knowledge from various traditions. Muslim scholars actively translated and commented on Greek medical texts (Hippocrates, Galen), Persian works (Avicenna, Rhazes), and Indian medical treatises, integrating and enriching them with their own clinical observations and research. This intellectual dynamism, supported by the enlightened patronage of numerous Muslim rulers, laid the foundation for an innovative and organized healthcare system.

Religion itself played a fundamental role. Islam places great emphasis on charity, compassion, and the care of the sick, values deeply rooted in the teachings of the Qur’an and the Sunnah. This spiritual perspective on health and well-being significantly contributed to the rise of Bīmāristāns, which were often seen as tangible expressions of these religious values. The construction and operation of these hospitals were frequently motivated by a desire to serve the community and address a vital social need, encouraging patrons to invest heavily in these institutions.

Key figures supporting the establishment and expansion of Bīmāristāns included caliphs, sultans, and influential governors, often driven by the ambition to leave a lasting legacy and reinforce their legitimacy.

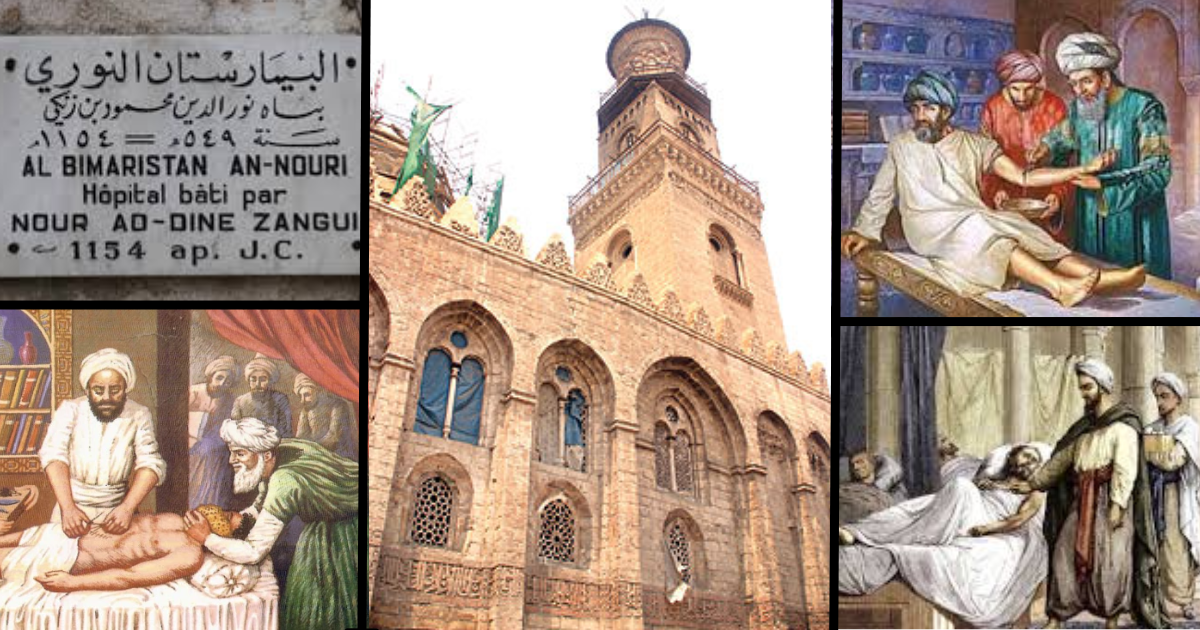

The first Bīmāristān, whose precise founding date is debated but generally placed in the 8th century in either Damascus or Baghdad (some sources suggest the first one may have been built in Gunbad-e Qabus in the 10th century), reflects the early commitment of Islamic civilization to medical care and research. This pioneering institution paved the way for the construction of numerous similar establishments across the Muslim world, significantly contributing to the preservation and advancement of ancient medical knowledge and its transmission to Europe.

In Baghdad, under the Abbasid Caliphate (8th–13th centuries), multiple Bīmāristāns operated, including one founded by vizier Nizam al-Mulk, which featured specialized wards for various diseases, pharmacies, and accommodations for both staff and patients. Detailed descriptions of these institutions, along with references in the writings of physicians such as Al-Razi (Rhazes), attest to their significance.

In Damascus, another key city of Islamic civilization, important Bīmāristāns were established under various rulers from the 8th century onward. Many were funded by waqfs (religious endowments), and archaeological and literary evidence confirms their role in the city’s medical landscape.

In Cairo, during the Mamluk era (13th–16th centuries), several Bīmāristāns were closely associated with mosques and religious complexes. These hospitals were regarded as pious endeavors, reflecting the strong patronage of the time. The Mansuri Hospital in al-Mansuriyya is a well-documented example.

To the west, in Marrakech, under the Almoravid and Almohad dynasties (11th–12th centuries), numerous hospitals existed, though fewer historical details survive. However, their presence illustrates the significant role medicine played in this influential city.

Al-Andalus, the Muslim-ruled region of Spain, was a hub of intellectual and scientific flourishing. Major urban centers such as Córdoba, Seville, and Granada played a crucial role in medical advancements. Renowned physicians such as Avenzoar and Averroes, who practiced in Seville and Córdoba, exemplify the sophistication of medical knowledge in this period. While direct evidence of Bīmāristāns in Al-Andalus is lacking, the widespread patronage of charitable institutions and the close ties to the broader Muslim medical world make it highly plausible that similar structures provided high-quality healthcare to the Andalusian population.

Beyond rulers, wealthy merchants, scholars, and philanthropists also contributed to the funding and management of Bīmāristāns, reflecting a collective commitment to public well-being. Their financial support enabled not only the construction of these hospitals but also the employment of skilled medical staff, the acquisition of medicines and instruments, and the funding of medical research. The history of Bīmāristāns is thus deeply intertwined with the history of patronage and philanthropy in the medieval Islamic world.

Healing the mind: how Bīmāristāns pioneered mental health care

Far from being mere hospitals, Bīmāristāns functioned as comprehensive medical centers offering a broad range of services beyond physical care. These institutions, particularly in Baghdad, Damascus, and Cairo, featured specialized treatment rooms, well-stocked pharmacies with botanical, mineral, and animal-based remedies, surgical rooms when needed, extensive medical libraries, and lecture halls for student training. Patients also received accommodation, meals, and spiritual support, reflecting a holistic approach to healthcare that considered overall well-being.

Mental health care was an integral part of this approach, even in the absence of modern psychiatric concepts. Medieval physicians recognized the deep connection between the mind and body. Mental disorders, seen as imbalances, were treated through a multidisciplinary approach, including personalized diets, tailored physical activities, music therapy, and artistic expression (such as calligraphy or painting) to encourage relaxation. Conversations akin to modern psychotherapy were also conducted by skilled physicians like Avicenna, whose writings demonstrate a profound understanding of emotional states and their effects on physical health. The aim was to alleviate suffering and improve patients’ quality of life through methods that harmonized body and mind.

Medical staff were diverse in origin and expertise, comprising physicians diagnosing and treating illnesses, surgeons performing complex procedures, pharmacists preparing and administering medications, nurses providing direct care, and administrators managing hospital operations.

Healthcare was often free for the impoverished, while wealthier patients could access private rooms and additional services. This inclusive structure underscores the Bīmāristāns’ commitment to the well-being of the entire population, both physically and mentally.

How Bīmāristāns shaped modern medicine

The Bīmāristāns, as pioneering medical institutions of the medieval Muslim world, left a profound and lasting legacy that shaped the development of medicine beyond the Islamic world. Their influence extended to Europe, where their model played a pivotal role in the evolution of modern healthcare systems. The holistic approach of Bīmāristāns, integrating both physical and mental healthcare, laid the groundwork for organized and humanistic medicine. Their structure, featuring specialized wards, pharmacies, libraries, and physician training programs, inspired the founding of Europe’s first hospitals, such as Hôtel-Dieu in Paris and Santa Maria della Scala in Siena.

A particularly remarkable aspect of Bīmāristāns was their compassionate treatment of mental illness, an approach that was revolutionary for the time. Patients with psychological disorders received therapies involving music, discussions, and calming activities, a vision that foreshadowed modern psychiatric care. Today, mental health institutions increasingly reintegrate such practices, including art therapy and mindfulness, echoing the innovative methods of medieval Bīmāristāns.

Recognizing the contributions of Bīmāristāns and medieval Muslim scholars is essential in understanding the multicultural foundations of modern medicine. Their legacy is not just a historical footnote, it is a timeless source of inspiration for the future of healthcare.

References

Avicenne (Ibn Sina) (1025). “The Canon of Medicine (Al-Qanun fi al-Tibb)”.

Dols, Michael W. (1987). “The Origins of the Islamic Hospital: Myth and Reality”. Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 61(3), 367-390.

Horden, Peregrine (2008). “Hospitals and Healing from Antiquity to the Later Middle Ages”. Ashgate Publishing.

Pormann, Peter E., and Savage-Smith, Emilie (2007). “Medieval Islamic Medicine”. Edinburgh University Press.

Ragab, Ahmed (2015). “The Medieval Islamic Hospital: Medicine, Religion, and Charity”. Cambridge University Press.

Savage-Smith, Emilie (1996). “Medicine in Medieval Islam”. In The Cambridge History of Science, Volume 3. Cambridge University Press.

Amine Lahhab

Television Director

Master’s Degree in Directing, École Supérieure de l’Audiovisuel (ESAV), University of Toulouse

Bachelor’s Degree in History, Hassan II University, Casablanca

DEUG in Philosophy, Hassan II University, Casablanca