The Walkman: From shared melody to solitary symphony

Some revolutions don’t knock. They slip quietly into our daily lives, unnoticed at first, until we can no longer live without them.

In 1979, Sony introduced a device with an almost unremarkable name: the Walkman. But behind this modest word lay a quiet metamorphosis. For the first time, music broke free from living rooms, records, and crowded gatherings. It became portable, personal, secret. A soundtrack for our thoughts. A sonic refuge we could carry anywhere.

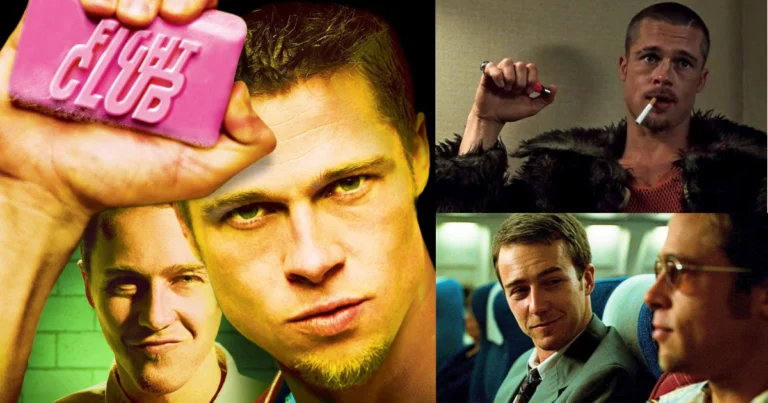

Beneath the shelter of headphones, each person became the narrator of their own story, the protagonist of an invisible film. The Walkman didn’t just change how we listened. It opened an inner world, shaped by songs no longer shared.

Before the Walkman: Music as a shared experience

There was a time when listening to music wasn’t a private choice but a communal moment. In many households, the radio held a central place in the living room. Later, vinyl records spun in shared spaces, heard by everyone, discussed, debated. Music was a social event, sometimes even involuntary. It accompanied family dinners, lazy Sundays, and evenings with friends. It belonged to the collective sphere, not the personal.

Until the 1970s, musical listening was fundamentally ritualistic and shared. It happened around a turntable, at concerts, or while waiting for a radio broadcast. Even in restaurants or cafés, the jukebox allowed users to choose a song, but only by exposing that choice to everyone in the room. To choose was to impose: your track became the group’s soundtrack. The desire for individuality was there, but by default, it remained public.

We danced to the Beatles, we cried together over Brel or Piaf. Even the emotions music evoked were collective, visible, and shared.

In that world, there were no headphones. No acoustic refuge. We listened to connect, not to retreat.

And then, one day, music stopped floating in the room, it slipped into our ears. This shift didn’t just alter how we listened; it changed the place music held in our inner lives.

The Walkman: An intimate object, a portable world

When Sony released its first Walkman in 1979, the TPS-L2, a small blue device with two headphone jacks, no one yet grasped the magnitude of the transformation. It wasn’t just a portable player. It marked a paradigm shift. For the first time, music became truly mobile, personal, and customized. Listening moved from public spaces to the privacy of headphones. The Walkman didn’t add another listening mode; it invented one: chosen solitude.

This shift ran deep. It was no longer just about hearing a song, it was about syncing it to your own pace, your own path. You could walk, run, dream, cry, in a world that belonged only to you. The cassette was no longer a shared object but an extension of identity. You weren’t listening to music. You were listening to your music.

The massive success of Thriller, Michael Jackson’s iconic 1982 album, perfectly illustrates this change. Far from collective turntables, millions discovered Beat It and Billie Jean through headphones, in buses, on sidewalks, while walking. The album became a personal soundtrack, an interior moment rather than a social event.

With the Walkman, a new era began, one in which we no longer shared music but slowly folded into it, as into a shelter.

A new psychological space: Listening becomes self-listening

With the Walkman, music ceased to be just something heard, it became a tool for emotional self-regulation. Listening was no longer dictated by one’s environment, but by one’s internal state. The Walkman allowed people to curate their moods: a melancholic song for a solitary walk, an energizing track to start the day. Music became an intimate lever, a kind of personal emotional pharmacy.

Sociologist Michael Bull (2000), a leading researcher on mobile technologies, described this as mood management through sound. Users selected tracks to build emotional bubbles adapted to each moment of daily life. Shuhei Hosokawa (1994) coined the term audio-topia to describe this phenomenon: a floating psychic space carried along with the listener, where reality is filtered, colored, and made more bearable through sound.

Tia DeNora (2000) showed that music structures our routines and emotions, shaping social interactions, even gestures. The Walkman turned listening into a continuous internal dialogue, a mental soundtrack that redefined self-perception.

In this sense, listening became far more than hearing, it became a way of tuning in to oneself, through music.

Altered perception: The world becomes a soundtrack

The Walkman didn’t just transform music listening, it reshaped how we perceive reality. Through headphones, the city ceased to be a neutral space. It became a stage, projected outward from within. The sidewalk turned into a tracking shot. The way we looked at others changed, as if every scene of daily life was now filtered through an invisible score.

Philosopher Peter Sloterdijk might describe these as immunological bubbles: sensory capsules we create to buffer ourselves from the shock of the world. Headphones function as psychic regulators. They don’t transmit reality, they sculpt it. Philosopher Michel Serres spoke of our modern need to filter chaos through sensory mediations. In this sense, music becomes an existential navigation tool.

That’s why today’s Spotify trend of “city soundtracks” makes perfect sense, playlists designed for walking through Tokyo, strolling in Lisbon, or waiting for nightfall in Berlin. They reflect a profound shift: we’re learning to sonify and script our environments. To treat reality as a lived fiction, staged inwardly and carried by sound.

It is no longer the environment that sets our mood, it is our mood that seeks the right soundtrack. Music doesn’t reflect the world. It reinvents it.

Composing for headphones: When listening shapes creation

If the Walkman transformed how we listen, it also subtly altered how music is composed. When music becomes intimate, mobile, and fragmented, composers no longer write for concert halls but for solitary ears in motion. They no longer address a crowd, but a passerby, a passenger, a student focused beneath their headphones.

By the 1980s, a more introspective, textured kind of music began to emerge, designed to be lived in the quiet of one’s inner world. Brian Eno led the way with Music for Airports (1978), which he described as “ambient music,” crafted to float within the listener’s mental space. Sound became landscape.

This sensibility influenced artists like Moby, whose album Play (1999) blended blues samples, electronic layers, and urban solitude. Or Boards of Canada, whose sonic textures evoke buried memories, as if the music were emerging from distant recollections.

Composers now imagine music as a sensory environment, an inner soundtrack. Tracks don’t seek to captivate. They accompany, envelop, suggest. It’s music for thinking, walking, dreaming.

In this sense, the Walkman didn’t just transform how music is received. It altered music itself. The artist no longer creates a piece, they sculpt an atmosphere.

Dressing reality

Perhaps this small gesture, putting on headphones, selecting a song, walking through the world in silence, is simply the latest expression of a much older need: the desire to never face reality bare. To cover it in images, stories, and sounds. To cross through it under a chosen, protective veil.

The Walkman inaugurated this modern form of active withdrawal. Not a flight, but a recomposition. Not abandonment, but reinterpretation. And through this act, the world becomes more inhabitable.

Today, more layers are coming: augmented reality headsets, immersive sound environments, simulated worlds where perception and illusion blur. Which leaves us with one lingering question: after so many overlays, will we still recognize the real world when we meet it?

Références

Bull, M. (2000). Sounding Out the City: Personal Stereos and the Management of Everyday Life. Oxford: Berg.

Bull, M. (2007). Sound Moves: iPod Culture and Urban Experience. London: Routledge.

DeNora, T. (2000). Music in Everyday Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hosokawa, S. (1994). The Walkman Effect. Popular Music, 13(1), 165–173.

Serres, M. (1993). Les cinq sens: philosophie des corps mêlés. Paris: Grasset.

Sloterdijk, P. (2005). Sphères II : Globes – Macrosphère. Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

(Trad. française de Sphären II: Globen, 1999)

Amine Lahhab

Television Director

Master’s Degree in Directing, École Supérieure de l’Audiovisuel (ESAV), University of Toulouse

Bachelor’s Degree in History, Hassan II University, Casablanca

DEUG in Philosophy, Hassan II University, Casablanca