Reading minds in bone: The rise and fall of Phrenology

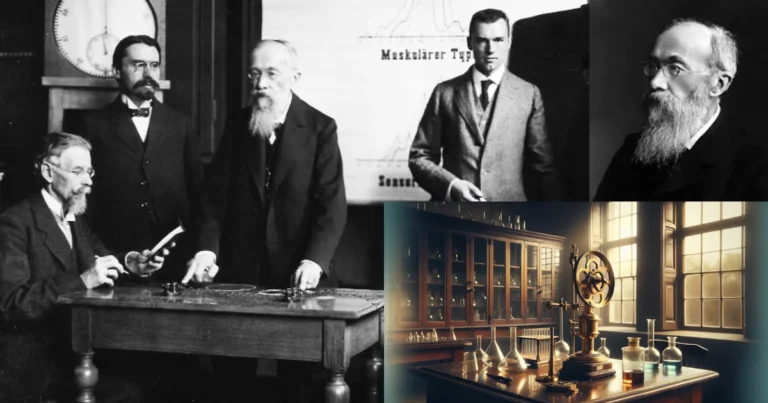

During a time when science was still struggling to unravel the brain’s mysteries, an idea both audacious and alluring began to take root. What if the shape of an individual’s skull could reveal their character and intelligence? In the late 18th century, the German physician Franz Joseph Gall proposed a hypothesis that would leave an indelible mark on the history of neuropsychology. He contended that our intellectual abilities, character traits, and even criminal inclinations were inscribed in the contours of our skull. This claim, later known as phrenology, sparked immediate enthusiasm, driven by the hope that science might finally decode the mysteries of the human soul. However, this fascination with cranial bumps did not emerge in a vacuum. Long before Gall, centuries of philosophical and scientific thought had already paved the way.

From Aristotle to Vesalius: The early quest to understand the mind

Since ancient times, thinkers have questioned the origin of thought and emotion. Aristotle, for example, believed that the heart was the seat of intelligence, while Galen, through his dissections of animals, began to suspect that certain parts of the brain might be responsible for specific functions. These ideas persisted into the Renaissance, an era when human anatomy took a great leap forward thanks to the dissections carried out by Andreas Vesalius. However, it was in the seventeenth century that thinking took a decisive turn with Descartes and his dualist theory, which posited that soul and body are distinct and connected by a mysterious junction: the pineal gland. Nevertheless, despite these advances, the notion that thoughts and emotions originate in the brain remained unclear. It was not until the eighteenth century and the rise of materialism that research adopted a more mechanistic approach, no longer viewing the brain as a shapeless mass but rather as a machine composed of various parts, each with a distinct role.

It is in this context that Franz Joseph Gall enters the scene. He extended his predecessors’ intuition by claiming that the brain comprises multiple independent “organs,” each associated with a specific function, memory, benevolence, aggression, spirituality, and so on. In his view, these areas develop differently from one person to another, pressing on the inside of the skull and creating surface contours that can be felt by touch. In other words, a simple tactile examination of the cranium could reveal the depths of the human soul as if reading an open book.

To make this theory more accessible and convincing, Gall and his student Johann Spurzheim created phrenological charts, detailed diagrams of the human skull in which each region is linked to a specific mental function. These charts were based on a rigorous subdivision of the brain, which, according to Gall, contains 27 distinct cerebral “organs.” Every region corresponds to a particular intellectual, emotional, or behavioral capacity, such as language, parental love, courage, ingenuity, or even a destructive instinct.

To make this theory more accessible and convincing, Gall and his student Johann Spurzheim created phrenological charts, detailed diagrams of the human skull in which each region is linked to a specific mental function.

These charts quickly became vital tools for phrenologists. Their success is owed not only to their educational value but also to their visual impact. By offering a graphic representation of how the brain might work, the charts lent phrenology an aura of scientific credibility that made it especially persuasive to the general public. They transformed abstract concepts into a tangible map of human personality, reinforcing the idea that character and intellect are measurable and predictable.

Armed with these materials, Spurzheim popularized the theory under the name “phrenology” and introduced it to Britain and the United States, where it became a genuine social phenomenon. Through their simplicity and apparent precision, the phrenological charts played a significant role in the spread of the discipline, which then emerged as a key reference in debates on human nature.

Phrenology fever: When society fell for cranial readings

By the early 19th century, phrenology was no longer confined to academic circles; it had become a genuine social craze. Head-reading sessions proliferated in both fashionable salons and popular fairs. Carried out by self-styled phrenologists, these consultations attracted people eager to unearth truths about themselves. Using their hands or specialized measuring instruments, these so-called experts claimed to reveal a client’s personality, hidden talents, and even professional prospects.

These head readings were not merely a form of entertainment. In an era defined by industrialization and the rise of the bourgeoisie, they became a practical tool for managing skills and determining social destinies. Some employers used them to vet prospective workers, convinced that skull shape could guarantee a candidate’s reliability and intelligence. Meanwhile, parents consulted phrenologists when deciding their children’s educational paths, hoping to identify future doctors, artists, or lawyers from an early age.

Phrenology also made inroads into the realm of romance. Certain individuals used head readings to gauge the compatibility of a potential marriage, believing that the shape of the skull might indicate fidelity, tenderness, or passion. Genuine phrenology offices sprang up in major cities across Europe and the United States, where consultants produced detailed reports on their clients’ personalities, futures, and moral character.

Beneath this apparent sophistication, however, lay a profoundly biased and easily manipulated practice. Phrenologists’ subjective judgments, compounded by the prevailing biases of the time, led to conclusions that often reinforced existing social inequalities. Gradually, phrenology became a tool for discrimination, serving to legitimize entrenched social hierarchies and justify eugenic policies.

The paradox of phrenology: A disproven theory that fueled modern science

Although phrenology soared to popularity in the 19th century, its decline was equally dramatic. As medicine and the science of the brain progressed, the foundation of this theory began to crumble, making way for a more rigorous, evidence-based approach. What once seemed like a revelation regarding human nature ultimately proved to be a major scientific misstep. Nevertheless, in a twist of irony, phrenology opened the door to groundbreaking discoveries that would revolutionize our understanding of the brain.

One of phrenology’s major flaws was its total lack of rigorous scientific methodology. Gall and his followers built their theory on empirical observations heavily influenced by subjective expectations. They did not employ controlled experiments or statistical methods to validate their claims. The notion that cranial bumps directly corresponded to underlying brain structures came under increasing scrutiny as autopsies and anatomical studies revealed that the skull’s surface offered no reliable indication of the brain’s internal organization.

At the turn of the 19th century, researchers such as Paul Broca and Carl Wernicke began to show, on far more solid scientific grounds, that certain cognitive functions truly do reside in specific regions of the brain. Broca identified a region in the left frontal lobe crucial to speech production. Building on that discovery, Wernicke demonstrated the existence of another region dedicated to language comprehension, thereby confirming that distinct language functions are associated with different areas of the brain. In contrast to phrenology, these findings were based on clinical observations of patients with brain lesions, allowing researchers to pinpoint precise connections between injured regions and the loss of particular cognitive abilities.

Paradoxically, if phrenology was one of the greatest scientific detours, it was also a starting point for a genuine revolution in neuroscience.

With the dawn of the 20th century, technological advances definitively buried phrenology while simultaneously validating its core intuition that specialized regions exist within the brain. The development of electroencephalography (EEG) and, later, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) enabled scientists to observe the brain in action, mapping the interconnections between different areas. They discovered that the brain functions not as an isolated patchwork of zones but rather as a dynamic network in which complex interactions give rise to cognitive processes.

Paradoxically, if phrenology was one of the greatest scientific detours, it was also a starting point for a genuine revolution in neuroscience. By introducing the idea that specific regions of the brain are linked to particular functions, it laid the groundwork for in-depth studies of functional specialization in the cortex. At the same time, phrenology’s aspiration to connect brain anatomy with human behavior inspired more serious, methodologically rigorous investigations into cognition, neuroanatomy, and neurological disorders.

Thus, the story of phrenology is that of a triumphant failure, an episode in which an appealing yet flawed theory shaped scientific thought for decades, only to be dismantled by empirical evidence. However, the mistakes of the past often serve as springboards for future discoveries. Modern neuroscience has revealed that human behavior cannot be reduced to cranial bumps but rather emerges from a complex interplay of neural activities and connections, far more captivating than anything Gall could have imagined. In an ironic turn, while attempting to map the human mind with rudimentary tools, phrenology ultimately inspired some of the most advanced techniques now used to explore one of science’s greatest mysteries: the brain.

References

Jefferson G. The contemporary reaction to phrenology. (Ludwig Mond Lecture, 1955.) Selected Papers. London: Pitman, 1960; 94–112.

Simpson, D. (2005). Phrenology and the neurosciences: Contributions of F. J. Gall and J. G. Spurzheim. ANZ Journal of Surgery, 75(6), 475-482

Sara Lakehayli

PhD, Clinical Neuroscience & Mental Health

Associate member of the Laboratory for Nervous System Diseases, Neurosensory Disorders, and Disability, Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy of Casablanca

Professor, Higher School of Psychology