Falling down: when one man’s collapse mirrors a society in crisis

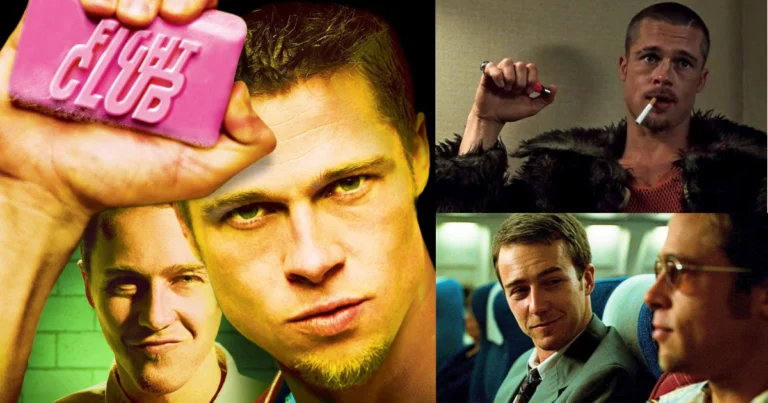

What if a simple traffic jam was all it took to push an ordinary man over the edge? Falling Down, directed by Joel Schumacher in 1993, stars Michael Douglas as William Foster, a seemingly average man who spirals into violence after a cascade of everyday frustrations. More than just a psychological thriller, this cult classic offers a compelling exploration of the brain’s response to stress, anger, and disillusionment. This article examines how Falling Down illustrates key concepts in psychology and neuroscience, decoding the mental disorders, emotional reactions, and cognitive processes that drive Foster’s breakdown.

Behind the madness: the making of Falling down

Released in 1993, Falling Down is a psychological thriller directed by Joel Schumacher, known for films such as The Client and Batman Forever. Written by Ebbe Roe Smith, the original screenplay drew inspiration from the social and economic tensions of early 1990s America, a period marked by mass layoffs and growing societal disillusionment.

Schumacher was drawn to the project for its social relevance and bold portrayal of suppressed rage. He saw in it a chance to question societal norms and portray the psychological breaking point of an individual under pressure. Michael Douglas, cast as the protagonist William Foster, was intrigued by the role’s complexity. In interviews, he noted that the character allowed him to explore darker, more vulnerable aspects of the human condition, far removed from the heroic roles that had defined his career.

Filming took place in Los Angeles, a city chosen for its symbolic weight. Often seen as the embodiment of the American dream, LA becomes, in the film, a chaotic and oppressive landscape mirroring Foster’s mental state. Schumacher insisted on shooting key scenes in real locations, such as a fast-food restaurant and a gun store, to heighten the story’s realism.

The film’s iconic opening traffic jam scene was shot in real conditions, with unsuspecting drivers caught in gridlock unaware they were part of a film shoot. This added an authentic layer of tension to the sequence.

A day in hell: when every frustration ignites

The story follows William Foster, a laid-off defense engineer, who unravels into violence during a single, unbearably frustrating day. It all begins in a traffic jam, under the sweltering Los Angeles sun, when Foster abandons his car and sets off on foot. Each encounter, a fast-food restaurant, a weapons shop, a city park, ignites his mounting rage. The ordinary man transforms into a vigilante, confronting a society he deems corrupt and unjust.

The film explores the limits of human tolerance and the devastating effects of chronic stress, while sharply criticizing social inequality and the banal frustrations of everyday life.

The American dream fractured: A 90s tale of disillusionment

Disillusionment lies at the heart of the film. Foster embodies the average man who once believed in the promise of the American dream, a steady job, a united family, and a meaningful place in society. As the narrative unfolds, he realizes those ideals have crumbled.

Within the context of the early 1990s, his disillusionment reflects the broader socio-economic upheaval of the time. The U.S. faced a recession, with widespread industrial layoffs and rising unemployment. Men like Foster, once the backbone of the middle class, were cast out of the system, losing their jobs, status, and often their families.

The film expresses this disillusionment through powerful symbols: a fast-food restaurant that refuses Foster breakfast by a matter of minutes, a gun shop owner exploiting his distress, and blaring advertisements promising happiness in a world that has clearly abandoned him. These scenes illustrate the growing chasm between the promises of American life and everyday reality.

Ultimately, Foster’s disillusionment is not only personal, it is collective. It reflects a time when certainties were dissolving, the American dream seemed increasingly out of reach, and anger became a natural response to perceived injustice.

Stress and anger: a brain overloaded

William Foster is a fascinating case study in how the brain responds to chronic stress. Each frustration, from gridlock to a poorly made hamburger, triggers his amygdala, the brain’s center for emotions like fear and anger. Simultaneously, his prefrontal cortex, which regulates impulses, becomes overwhelmed, resulting in a loss of control.

Neuroscientific studies show that chronic stress can alter both the structure and function of the brain. Prolonged exposure to cortisol, the stress hormone, leads to a hyperactive amygdala and a weakened prefrontal cortex. This imbalance impairs emotional regulation. Foster exemplifies this process: after months of unemployment, isolation, and mounting frustrations, his brain no longer distinguishes between minor setbacks and genuine threats. Every obstacle, a traffic jam, a service refusal, feels like a personal attack, prompting disproportionate reactions. This emotional dysregulation plays a central role in his turn to violence.

A break from reality: when the brain loses its grip

One of the film’s most memorable scenes takes place in a fast-food restaurant, where Foster demands breakfast just minutes after the cutoff time. The setting is oppressive, flickering fluorescent lights, robotic staff, and a rigid rule: “Breakfast ends at 11:30.” Foster’s neutral expression slowly contorts with rage. Close-ups of his bloodshot eyes and trembling hands reveal a man on the edge. When he draws a gun to enforce his demand, the camera lingers on the counter, cold burgers and a spilled cup of coffee, symbolizing the absurdity of the moment.

This scene illustrates how a stressed brain can misinterpret reality. With his amygdala in overdrive and his prefrontal cortex impaired, Foster cannot distinguish a trivial frustration from an existential threat. His reaction, a violent outburst over breakfast, reflects a breakdown of inhibition, a key concept in neuroscience describing the collapse of moral and social restraints.

Psychologically, this moment marks Foster’s rupture with reality. Once a law-abiding citizen, he now disregards social norms entirely. Disinhibition like this often appears in individuals under extreme stress or with untreated mental disorders. It explains how Foster shifts so abruptly from an ordinary man to a dangerous vigilante, unable to foresee the consequences of his actions. The fast-food scene thus becomes a powerful metaphor for his mental collapse, with every detail reinforcing the image of a brain in overdrive, unable to restore balance.

Underlying mental illness: a diagnosis between the lines

Foster exhibits signs of undiagnosed mental illness, which likely play a central role in his unraveling. Several elements suggest he may be suffering from major depressive disorder and a personality disorder, possibly borderline or paranoid.

A deep sense of despair

Signs of depression emerge early on. Foster displays a clear loss of interest in his surroundings, chronic fatigue (reflected in his vacant gaze and slumped posture), and intense feelings of worthlessness, triggered by his layoff and divorce. These traumatic events act as catalysts, plunging him into despair. In one poignant scene, he gazes at a photo of his now-estranged family, overcome with a painful nostalgia and sense of failure, hallmarks of clinical depression.

Emotional fragility

Foster also exhibits traits consistent with borderline personality disorder: emotional instability, impulsivity, and a deep fear of abandonment. His inability to tolerate frustration, extreme reactions (as in the fast-food scene), and obsessive need to control his environment suggest profound vulnerability. His exaggerated mistrust of others and tendency to perceive benign actions as personal attacks may also point toward paranoid traits.

His dismissal and divorce serve as accelerants, magnifying preexisting conditions. Losing his job not only erodes his self-esteem but also deprives him of the structure that emotionally fragile individuals often rely on. The loss of his family further isolates him, stripping away crucial social support. Without intervention, these compounded stressors push him past the tipping point.

Crucially, Falling Down highlights the absence of medical or psychological care for Foster. In a time when mental health was still stigmatized, his symptoms likely went unrecognized. This lack of support partly explains the abruptness of his breakdown, without help, his condition worsens, leading to a full rupture from reality.

In the end, Foster represents someone grappling with untreated and unrecognized mental illness, destabilized by external stressors. His story underscores the critical need for prevention and mental health care, especially in times of socio-economic hardship.

A disturbing empathy: interpreting the film

Falling Down throws viewers into a whirlwind of emotion, evoking an unsettling empathy for Foster. His rage and frustration feel tangible, you may even find yourself sympathizing with his plight, while recoiling at his violent escalation. Upon its release in 1993, the film sparked controversy. Critics were divided: some accused Schumacher of glorifying violence, presenting Foster’s rage as a nearly justified response to modern life’s frustrations. Others warned against the dangerous normalization of antisocial behavior, stressing that Foster, despite some sympathetic traits, remains a deeply troubled character.

Despite these debates, Michael Douglas’s riveting performance and the film’s social resonance earned it critical acclaim and cult status. To this day, Falling Down continues to provoke passionate discussion, particularly about its portrayal of anger, disillusionment, and the delicate boundary between empathy and the glamorization of violence.

Sergeant prendergast: A lighter reflection of stress response

In stark contrast to Foster stands Sergeant Prendergast, played by Robert Duvall, a portrait of resilience and emotional balance. While Foster succumbs to frustration and violence, Prendergast, facing his own struggles, a mentally ill wife and an impending retirement that threatens his sense of identity, remains grounded.

Often reserved but always present, Prendergast acts as a foil to Foster. He embodies the strength found in healthy coping mechanisms and social connection. He acknowledges his difficulties but meets them with calm determination. He maintains a delicate equilibrium between personal and professional responsibilities, showing that resilience doesn’t mean avoiding stress, but navigating it wisely.

Prendergast represents a glimmer of hope in a bleak, disillusioned world. He reminds us that even amid life’s harshest trials, it is possible to remain humane, regulate one’s emotions, and find meaning through connection. His presence offers a nuanced conclusion: while Foster illustrates the perils of isolation and unchecked despair, Prendergast stands as proof of enlightened resilience, anchored in compassion, stability, and perseverance.

Amine Lahhab

Television Director

Master’s Degree in Directing, École Supérieure de l’Audiovisuel (ESAV), University of Toulouse

Bachelor’s Degree in History, Hassan II University, Casablanca

DEUG in Philosophy, Hassan II University, Casablanca