Chaïbia Talal: Where Pain Becomes a Palette

Far from being merely a strange or eccentric aesthetic, art brut opens a rare window onto the inner workings of subjectivity. These works are not to be viewed as symptoms to decode, but rather as singular attempts to hold together an often fragmented inner world.

This article explores how, in psychosis, art can take on the role of the sinthome, a Lacanian concept describing a unique, personal solution to a structural impossibility. Through this lens, we turn our focus to Chaïbia Talal, a self-taught Moroccan painter whose work sits at the intersection of art brut and extreme subjective experience.

A life outside the frame

Born in 1929 in a small village near El Jadida, Morocco, Chaïbia Talal grew up without formal schooling. Married at thirteen, widowed at fifteen, and left to care for a child, she worked as a housekeeper to support her family. By all accounts, nothing in her background pointed toward a future as an artist.

Everything changed after a vivid dream in which spiritual figures instructed her to paint. With no academic training and no ties to conventional artistic traditions, Chaïbia began creating. Her paintings were born of impulse, unpremeditated, raw, and unfiltered by mainstream artistic norms. When asked about her creative process, she simply replied, “I don’t think. God guides me.”

From her earliest canvases, her style burst forth: bold colors, stylized figures, dreamlike scenes where humans blend with nature in an exuberant display of life. Often grouped under the label of naïve art, her work resists simplistic categorization.

Painting as a pulse: The body speaks in color

For Chaïbia, painting was never a hobby or aesthetic pursuit, it was a necessity, an act as vital as breathing. Her art emerged as a primal gesture, almost bodily, driven by instinct and desire.

With no classical perspective or preparatory sketches, she filled the canvas with recurring figures, faces, gardens, suns, carried by raw energy and explosive lines. Her work doesn’t seek to represent the external world but to shape a deeply personal vision of it.

In this sense, painting became a way for Chaïbia to manifest her subjectivity, a way of existing in a world that had denied her the usual paths to recognition: education, speech, social integration.

Color as resistance, creation as healing

Chaïbia’s life was marked by early loss, social isolation, and precarity. However, these wounds are not directly depicted in her art. Instead, they are transmuted into a luminous universe, filled with joyous shapes and vibrant colors. In Freudian terms, one might say she achieved a form of sublimation, channeling traumatic energy into creative output. Her work does not dwell in sorrow; it celebrates an indomitable life force.

Here, sublimation is not a process of social normalization, but a profoundly intimate invention, an existential act by which the artist reclaimed her being in the face of absence and exile.

She painted to exist: A woman without labels

As a self-taught, illiterate woman from rural Morocco, Chaïbia Talal fits none of the traditional molds of the artist. Though she was eventually noticed by critics and artists like Ahmed Cherkaoui, and exhibited in France, the United States, and Europe, she always remained outside conventional systems.

Her work resists co-optation: too expressive to be conceptualized, too unbound to be folklorized. She embodies a radical form of feminine subjectivity, untethered from academic or market constraints, driven solely by inner urgency.

Chaïbia did not paint to communicate. She painted to exist. Each canvas is a surface of survival, a space where the self is reassembled through gesture.

Chaïbia and the Sinthome

From a Lacanian perspective, Chaïbia’s art can be seen as the elaboration of a sinthome, not a pathological symptom to be cured, but a unique invention that sustains the subject’s being.

Deprived of traditional symbolic anchors, she forged her own access to the world, weaving together the Real of trauma, the Imaginary of fantasy, and a personal Symbolic, one not inherited from dominant cultural norms.

The dream that triggered her creative impulse marks a moment of radical subjectivation. Through painting, she assigned herself an existential mission, rewriting a life that could otherwise have dissolved into silence.

When madness paints back

Historically, psychiatry has marginalized, pathologized, or co-opted the artistic expressions of those living on the edge of mental illness. Nevertheless, the act of creating can offer a form of stabilization, a fragile boundary against collapse.

From this perspective, Chaïbia’s work is a border act, a tenacious edge drawn against an unmediated real. Still, when such works enter institutional art circuits, they risk being neutralized, reduced to aesthetic objects and stripped of their radical force. Despite growing recognition, Chaïbia remained faithful to the source of her art, never compromising its origin.

To be, against all odds

Chaïbia Talal’s journey reminds us that what is often labeled marginality or inner excess is not merely disorganization, it can be the crucible of a radical invention of the self. Where language fails to hold the tumult of experience, art becomes a vital act, a silent writing, a symbolic skin, a trace left in an otherwise inhospitable world.

The sinthome, as Chaïbia illustrates, is not something to interpret or correct. It is a way of existing, a creative discovery carved from the impossible. Her work stands as a powerful testament: even in the most extreme conditions of social and symbolic abandonment, creation can arise as an affirmation of the self, a gesture of resistance against erasure.

Excerpt from a forthcoming book titled Art and Psychosis.

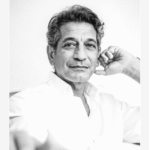

Hamid Cheddadi

Clinical Psychologist and Visual Artist

• Born on June 15, 1955, his journey bridges the realms of art, healing, and thought.

• Trained in the 1980s at the Poh Chang Academy of Arts in Bangkok, he developed a pictorial sensitivity deeply influenced by Asian aesthetics and spontaneous expression.

• As a painter, he explores the bodily and spiritual dimensions of therapeutic practice.

• He earned a diploma in osteopathy in Chiang Mai in 1992.

• Certified therapeutic yoga instructor (healing art), drawing inspiration from Japanese traditions.

• Former lecturer at ITM (Information Technology Morocco).

• Holds a Master’s degree in Clinical Psychology from the École Supérieure de Psychologie de Casablanca, practicing as a clinical psychologist.

• His therapeutic approach unfolds at the crossroads of art, the unconscious, human suffering, and spirituality.

• He lives and works in Casablanca, where he continues to paint, care, write, and share his knowledge.