When academic failure becomes more than a grade

She was only 14. That morning, she woke up like any other day. But something had changed. The day before, the results came in, she had failed her final exam for the third year of middle school. A single word, failure, and her world crumbled. A few hours later, she climbed to the third floor of a building… and jumped.

This is the heartbreaking story of a teenage girl from El Jadida. Not a young girl who rejected life, but a child who believed she no longer deserved it. She thought she had let everyone down: her parents, her teachers, those closest to her, and perhaps most painfully, herself.

To her, failing an exam wasn’t just a temporary setback. It was a serious offense. A stain on her self-image. A final judgment. It wasn’t failure itself that broke her, it was the weight attached to it. What the failure seemed to mean in others’ eyes, and in her own. Because too often, a child’s emotional response doesn’t arise from reality, but from the mirror adults hold up to them.

When love comes with conditions

Academic failure, in itself, is neither a catastrophe nor a life sentence. What makes it so painful is the way it is perceived, interpreted, and above all, received. In many families, the demand for success is deeply tied to parental love. Children are pushed to exceed expectations, not out of cruelty, but out of concern for their future. They are praised when they succeed, and reprimanded when they fail, under the sincere belief that this will help them grow.

However, what the adult intends to convey, “I’m doing this for your own good”, can be interpreted by the child or adolescent as: “If I fail, I don’t deserve to be loved.”

This misunderstanding stems from emotional conditioning. From an early age, children learn to associate attention, recognition, and affection with their accomplishments. If praise only comes with good grades, and tension rises when they don’t perform, a dangerous belief takes hold: “I am loved when I succeed.” Love then appears conditional on performance.

Gradually, school stops being just a place for learning, it becomes a place where one’s worth is measured. A bad grade is no longer a minor bump in the road; it becomes a threat to emotional security. The child isn’t just afraid of failing academically, but of what that failure might trigger in others’ eyes. It’s not just a report card on the line, it’s their very right to love, attention, and support.

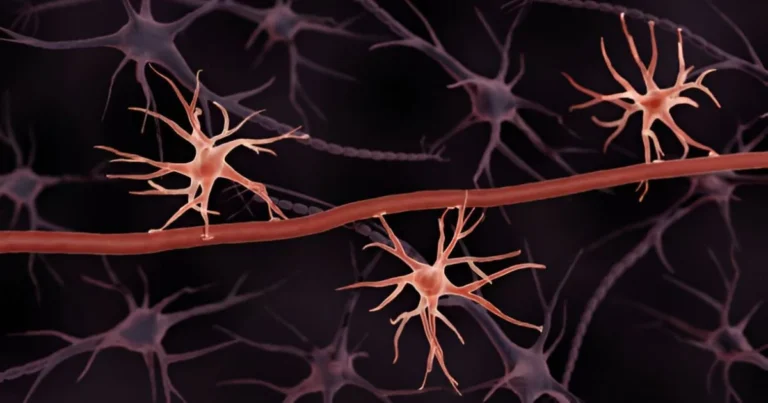

This emotional pattern becomes even more deeply rooted in adolescence, a time of heightened emotional vulnerability and intense brain restructuring. The teenage brain is still under construction: emotion-processing areas like the amygdala become highly reactive, while the prefrontal cortex, responsible for reasoning, self-regulation, and perspective, is still maturing. This imbalance makes teens more sensitive to outside judgment, criticism, and failure.

In this context, a bad grade, repeating a year, or even a seemingly harmless comment can take on exaggerated proportions. It’s not just the mistake that’s experienced, but everything it seems to threaten: self-worth, family belonging, self-esteem, and sometimes even group identity. At a time when identity is being shaped, failing an exam can feel like an emotional threat, far more than just a hurdle to overcome.

Families and educators are rarely operating from a place of punishment. On the contrary, their expectations are often motivated by love and care. But the messages they send can unwittingly create overwhelming pressure. Telling a child, “You need to succeed to get ahead,” can, in the impressionable mind of a teenager, sound like: “Only success grants you social legitimacy.” Failure, then, stops being a normal part of the journey and starts to feel like a moral shortcoming.

🔗 Read also: Teens, AI, and the death of effort? Rethinking learning in the age of ChatGPT

The education system itself functions under constant pressure. Teachers face overcrowded classrooms, dense curriculums, and ever-rising performance standards. Under such strain, it becomes difficult to address each student’s emotional and cognitive needs. Schools, meant to be spaces of growth and development, often focus on numbers and results at the expense of human connection and listening.

When a student fails, it’s not always seen as a cry for help or a signal of distress, but more often as a lack of effort or discipline. It’s all too easy to assume a student “didn’t work hard enough” or “didn’t care,” without pausing to consider the underlying reasons. And yet, as Daniel Favre reminds us, error is not the opposite of knowledge, it is its condition. Learning means stumbling, trying, failing, and starting again. We learn by confronting mistakes.

Despite progress in the psychology of education, this understanding remains underutilized in daily practice. Mistakes are still too often penalized with discouraging grades, repeating a year becomes an implicit punishment, and praise is mostly reserved for those who succeed according to conventional standards. Conformity is rewarded far more than effort, and quiet progress often goes unnoticed. In such a system, students receive a powerful implicit message: your worth is measured by your average.

For adolescents, already navigating intense social dynamics, every grade, every report, every evaluation carries symbolic weight far beyond its academic value. To them, failure is not just a problem in a subject, it threatens their self-worth, their place in their family, their group, their community.

We must understand that these wounds are not inflicted by malicious adults. They result from collective mechanisms, often driven by good intentions, that are misaligned with children’s psychological realities. No one sets out to harm. But harm is done, day after day, by clinging to rigid norms and forgetting that every learning journey is unique.

🔗 Explore further: One day one story: Building brains through books

What if failure were a step, not the end?

Transforming how we view academic failure is not simply about easing the pressure on students. It requires a fundamental shift in our entire educational culture. As long as mistakes are seen as weakness or defects to correct, students will fear them instead of embracing them as a part of their growth. This is directly opposed to what neuroscience teaches us today.

Far from being mere missteps, errors are the very fuel of learning. The human brain doesn’t learn in a linear or perfect way. It learns through trial, error, and adjustment. Each time we make a mistake, specific circuits in the brain are activated, especially those involved in error detection and prediction updating. These mechanisms allow the brain to identify what went wrong, compare expected with actual results, and gradually revise its internal models. In short, mistakes are not anomalies, they are essential to learning.

But for the brain to benefit from mistakes, the emotional climate must support it. If error is associated with shame, fear, or judgment, the brain doesn’t activate learning circuits, it triggers stress and avoidance. The student stops trying. Stops taking cognitive risks. Retreats. And a child who no longer dares to make mistakes, no longer dares to learn.

That’s why relational support is so crucial. Few children know they can make mistakes without losing the love or respect of those around them. Few adolescents know they can express sadness, disappointment, or confusion without being seen as weak or ungrateful. In families where emotions are avoided, or worse, where vulnerability is mistaken for moral failure, suffering children often fall silent. They don’t ask for help, not out of apathy, but because they believe it would make things worse.

This calls for a deep reevaluation of how we teach, assess, and support students. It starts with a change of perspective: restoring the value of mistakes, giving effort the recognition it deserves, and respecting slow progress just as much as quick performance. But it also means clearly separating a child’s worth from their academic results. Parental love cannot depend on rankings. Social esteem should never be built on the humiliation of those who move at their own pace.

Changing the culture of education is essential, especially given the measurable psychological toll of academic stress. Recent research shows that when school-related stress becomes chronic and poorly regulated, it can seriously affect adolescents’ mental health. When students perceive school as a place of constant judgment, where every grade seems to determine their worth or future, their self-image can fracture. And if they feel alone under that pressure, the danger becomes very real.

🔗 Discover more: From breaking point to breakthrough: How crises shape us

It’s not the intensity of stress that destabilizes, it’s the absence of internal and external resources to face it. That’s where coping strategies, and what we call resilience, come in. When adolescents face failure, their responses vary. Some withdraw, judge themselves harshly, or escape into distractions. These are natural reflexes, but over time, they risk becoming emotional dead ends. Others, by contrast, manage to take a step back, seek help, reframe what they’re experiencing. They don’t erase the pain, but they find a way through it.

This resilience, the ability to weather storms without sinking, doesn’t mean we don’t suffer. It means we still believe, deep down, that falling is not the end of the story. That we can learn, get up, and try again. But this strength isn’t innate. It’s built, slowly, patiently, and often, it’s shaped through the gaze of others. When a child feels that the people around them still believe in them after they’ve failed, they begin to believe they can move forward again.

That’s why the presence of a kind adult, a parent, a teacher, a mentor, can change everything. Someone who doesn’t minimize the pain, but doesn’t dramatize it either. Someone who says: “I know this is hard, but I’m here. And you can start again.” Those simple words can become an anchor, a compass, a breath of air. We can’t remove all the obstacles in our children’s paths, but we can help them build the inner compass to navigate them.

The tragedy we’re discussing should not be seen as a tragic exception. It reveals the blind spots of a system that emphasizes competition over inner development. It reminds us that for some children, a poor grade can become an existential wound, especially when left unaddressed. The death of this young girl is a testament to a love miscommunicated, a fear of judgment, a world where the right to stumble is denied. Her action, as heartbreaking as it is, must serve as a wake-up call.

We must teach our children that failure is not a sentence, but a step. That they have the right to fall without being rejected. The right to ask for help without fearing judgment. The right to be loved, especially when they are most vulnerable. And above all, the right to never feel alone.

References

Liu, L., Wang, W., Lian, Y., Wu, X., Li, C., & Qiao, Z. (2023). Longitudinal Impact of Perfectionism on Suicidal Ideation among Chinese College Students with Perceived Academic Failure: The Roles of Rumination and Depression. Archives of Suicide Research, 28(3), 830–843.

Okechukwu, C. E., Dirisu, O. J., Agberotimi, S. F., & Asante, K. O. (2022). Academic stress, coping styles, and suicidal ideation in a sample of Nigerian university students. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1), 891.

Zhao, Y., Maes, J. H. R., & Li, X. (2023). Association of stress exposure and parental involvement with suicide risk among adolescents: A school-based study. medRxiv.

Sara Lakehayli

PhD, Clinical Neuroscience & Mental Health

Associate member of the Laboratory for Nervous System Diseases, Neurosensory Disorders, and Disability, Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy of Casablanca

Professor, Higher School of Psychology