Ideology redefined: The inner evolution of how we think

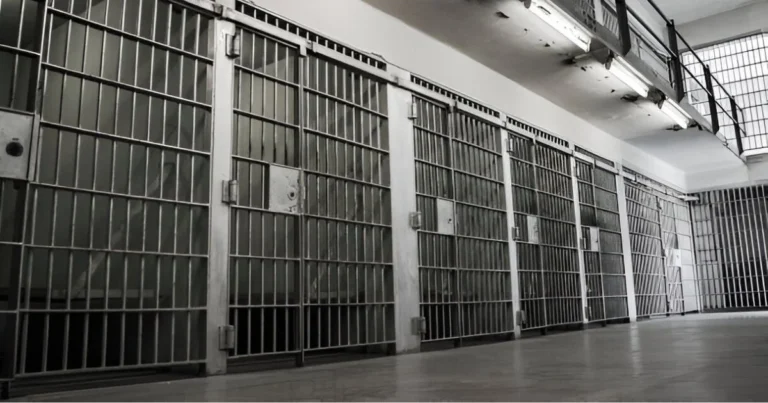

In the damp cell where he was imprisoned during the Terror, Destutt de Tracy, aristocrat, revolutionary, philosopher, and soldier, immersed himself in the works of Condillac. It was 1793, the darkest heart of the French Revolution: the Montagnard Convention, daily executions, pervasive fear. While many succumbed to terror or cynicism, he sought clarity in the chaos, a method to understand how ideas arise.

Formally suspected of noble birth and jailed without trial like so many others, he resisted political collapse by embracing a philosophical act of faith. For while the world crumbled outside, another revolution emerged within him: the revolution of thought that observes itself. In the tension between external terror and internal lucidity, he coined a new word: “ideology.” Not as dogma, but as science, a way to study ideas with the same rigor, detachment, and intent used for studying plants, minerals, or neural systems.

“Ideology,” then, was born in a cell, on the edge of the abyss, yet still fueled by Enlightenment breath. It aimed neither at power nor conversion, but to map the unseen springs of human representation.

How enlightenment thought gave rise to ideology

Under Napoleon, “ideologue” quickly becomes a term of disdain, an abstract thinker at odds with political will. From then on, ideology is no longer science but suspicion, doctrine, an instrument.

And yet it persists. It mutates, contaminates, pervades. Ideology isn’t a thought, it’s a mental structure, a worldview. It acts deeply through representations, emotions, decisions. It isn’t just what we think, it is what makes us think.

Ruins of hope: what remains of Metanarratives?

Historically, ideologies collapsed under their own contradictions. Marxism bred dehumanizing bureaucracies. Nationalism spawned wars and exclusions. Liberalism created massive inequality. Even cultural revolutions disappointed: institutional feminism diluted into marketing; ecology became a brand.

We live, as Lyotard put it, through “the end of Metanarratives.” Suspicion is omnipresent. Every ideology is seen as a mask or a power strategy. Nietzsche, Marx, Freud created tools of suspicion; Derrida, Foucault, Deleuze extended them. Every truth hides a will, every emancipation yields norms, every utopia manufactures exclusion.

🔗 Read also: Stronger than an Atom: Anatomy of a prejudice

Thus, ideologies haven’t died, they’ve decomposed organically. Their power shifted elsewhere. The post-ideological world is saturated, not empty. Filled with fragments, momentary causes, soft beliefs. Big narratives gave way to localized, identity-based, community-based stories. Activists morphed into influencers, hacktivists, vegans, survivalists, coaches. ZADs, crypto-communities, eco-spiritual tribes became sanctuaries.

But this fragmentation is dangerous. It blurs historical understanding, hinders long-term thinking, and thrusts us into immediacy. Ecological urgency, inequality, digital perils need systemic thought; instead, we patch with moral quick fixes, reactive indignations, truncated stories.

Yet ideologies still permeate our unconscious. They are dissolved in everyday life: desire for order (conservatism), belief in merit (liberalism), hatred of decay (fascism), call for equality (socialism), they resurface in discourse, slogans, algorithms.

The connected unconscious: when ideologies go algorithmic

Digital platforms have reinvented the art of ideological orientation. They don’t propose theses, they shape emotions, attention regimes, cognitive bubbles. They are belief matrices.

Debord’s “society of spectacle” has evolved into a “society of influence.” Once we sought truth; now, we seek visibility. Ideological narrative has become marketing script; political vision is storytelling.

The question is no longer “Which ideologies have we lost?” but “Which operate quietly within us?” In a classroom, a teenager feels stirred by some causes and indifferent to others, an emotional resonance precedes understanding. That is ideology: not reasoning but resonance.

Spinoza taught that ideas are never naked, they travel via emotions, anchored in bodies, stories, fears, hopes. We don’t join worldviews by reason alone, we enter them like a familiar home, warmed by an inner need, healed wound, or chaos ordered.

Neuroscience shows the human brain seeks coherence more than “truth.” It filters, associates, simplifies. Damasio found even rational choices are guided first by emotion. Ideology soothes internal tension by giving cause to fear or anger, a future to re-anchor anxiety.

Cognitive biases are not errors, they are structural to our judgments. Festinger’s cognitive dissonance (1950s) describes discomfort when actions contradict beliefs. To reduce this discomfort, we adjust perception. Ideology reassures, even at the cost of reality.

🔗 Explore further: The crowd: A study of the popular mind – A visionary look into group dynamics

Adherence is not only psychological comfort, it is also belonging. Nussbaum reminds us that collective emotions like shame, pride, anger, fuel “sensitive citizenship.” We feel left or right not just because we think it, but because we resonate with it. Ideology succeeds when it makes us feel seen, recognized, connected.

Why do some worldviews collapse while others rise? Culture plays a role. Bourdieu foresaw that beliefs root in “habitus”, lived styles, everyday language. Abstract, technical worldviews disconnected from ordinary experience fail. Simple, narrative visions find resonance in chaos.

Populism, conspiracy, identity narratives thrive on this gap. They offer comforting mental maps: heroes, enemies, clear causes, apocalyptic timelines, emotional scripts over doctrines.

Ideology, then, is not chosen, it is inhabited. It touches emotion and cognition in the thickness of living. As Castoriadis writes, ideology is a “social imaginary creation”, a need for order and meaning.

That’s why we’ll never be rid of ideologies, they respond to our need for orientation. They provide shelter, structure, direction. To avoid becoming prisons, we must question, update, revisit them constantly.

Living with our beliefs: a call for shared lucidity

Today, we must interrogate new beliefs: faith in salvific technology, self‑optimization, AI as the answer to human flaws. Not openly ideological, but massively influential, they produce hierarchies, exclusions, new symbolic subjugations.

Picture 3 AM in San Francisco: a screen’s bluish glow lights a silent office. A man leans over a keyboard, refining an internal manifesto on AI’s ethical potential. Sam Altman, OpenAI’s CEO, speaks of responsibility, civilization’s safeguard, aligning machines with human values. He thinks he’s forecasting the future, but he is weaving a narrative about us and what we should become.

Like Destutt de Tracy, Altman does not identify as an “ideologue.” Rational, prospective, science-moral at their crossroads. Yet behind the tech rhetoric lie the old building blocks: an implicit anthropology, a vision of progress, a grammar of salvation. Different century, same gestures. Ideology hasn’t disappeared, it merely wears a new skin.

🔗 Discover more: Exposing Authority’s Dark Side: Revisiting the Stanford Prison Experiment

Philosopher Nancy Fraser stresses that today criticism of ideology must extend to how subjects are shaped. How do systems produce a “self” compatible with platform capitalism? How do beliefs internalize as personal development, wellness, coaching, lifestyle?

Ideology, here, is no longer a program, it’s an atmosphere, a social mood, an implicit grid. It no longer needs manifestos, it permeates practices.

But can we live without ideology? Think without worldview scaffolding? Act without symbolic horizon? Without collective project?

That’s to imagine humans outside of culture. Everything we say is already a choice. Every story an exclusion. Every perspective an angle. Ideology is the very condition of collective thought. The problem is not its existence, but its unconscious dominance.

The aim is not to rid ourselves of ideology but to reclaim its use. To map our beliefs, reopen our collective imagination, restore the prospective function of thought.

Metanarratives were not mere power tools, they scaffolded meaning, held ethical laboratories, and inspired world transformation.

We don’t need dogmas, but we do need visions, shared meaning, compass points. Without them, we remain at the mercy of momentary impulses, permanent immediacy, symbolic atomization.

To rethink ideology today isn’t to rehabilitate it, it’s to reclaim it as a tool of mental resilience, a force for collective creativity, a space mediating desire and reality, self and world.

An ideology that doesn’t imprison or impose, but helps us see, choose, connect, act.

Ahmed El Bounjaimi

Copywriter-Content Designer

Master’s in Organizational Communication, Hassan II University

Bachelor’s in Philosophy of Communication and Public Spheres, Hassan II University