The self and its brain: Understanding duality according to Popper and Eccles

For millennia, humanity has been captivated by a profound question: what is the connection between our physical body and what we might call the essence of our being, our mind, our consciousness? This enigma dates back to ancient Greek philosophy, where thinkers offered divergent views. Plato conceived the soul as an immaterial and immortal entity, separate from the body. Aristotle, in contrast, envisioned a much more intimate interaction between the two realms.

This debate did not vanish with time. During the medieval Islamic Golden Age, prominent figures like Avicenna and Al-Farabi enriched the discourse. In his seminal Canon of Medicine, Avicenna described the brain as the seat of sensory and imaginative faculties, while attributing higher functions such as reason and intellect to an immaterial and eternal rational soul. Al-Farabi, meanwhile, delved into the nuances between human intellect and the “Active Intellect,” crafting a bold synthesis of philosophy and theology.

The 17th century saw the rise of René Descartes’ renowned dualism, which posited that the mind and body belong to distinct but interdependent realms. Today, the question remains central: with the rise of neuroscience, can we reduce the mind to mere neural processes? Or is there an immaterial dimension that transcends cerebral matter?

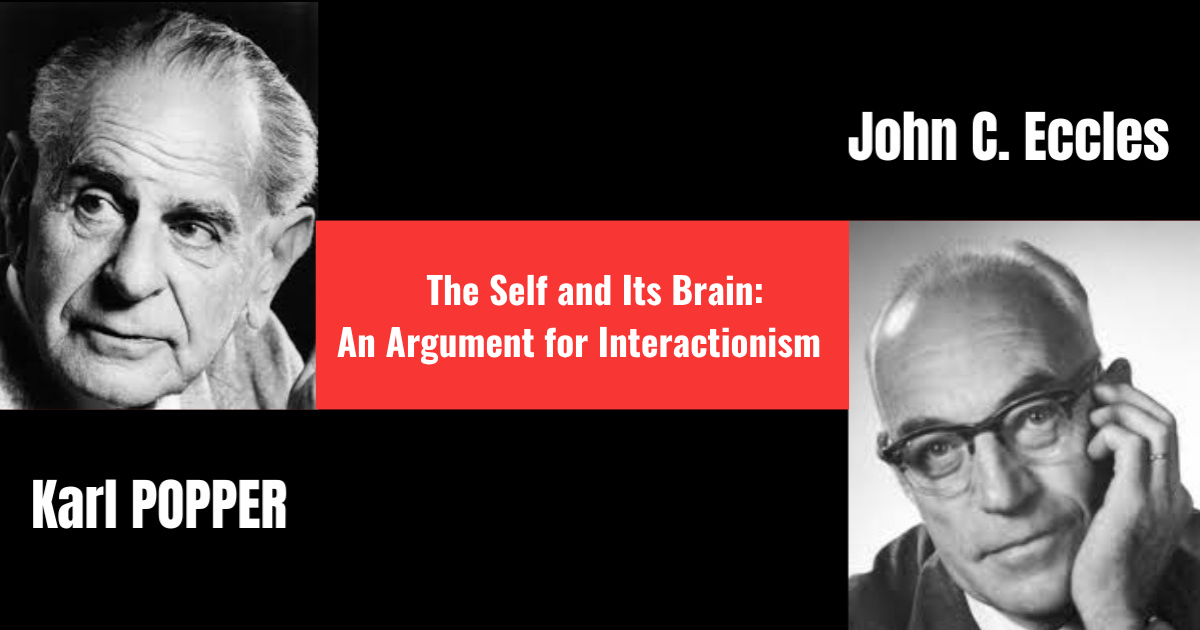

These enduring questions find a compelling voice in The Self and Its Brain (1977) by Karl Popper and John C. Eccles, a groundbreaking exploration of the dynamic interplay between mind and brain.

When science and philosophy collide: The 1970s breakthrough

The 1970s marked a transformative period for neuroscience. Breakthroughs in the biochemical mechanisms of the brain were revolutionizing our understanding of memory, perception, and cognition. However, this scientific surge also entrenched a materialist paradigm, one that sought to explain all mental phenomena through physical processes alone.

In response, philosopher Karl Popper and Nobel Prize–winning neurophysiologist John Eccles joined forces to propose an alternative: an interactionist theory in which the mind and brain engage in a dynamic and reciprocal relationship. The Self and Its Brain emerged from this interdisciplinary dialogue, blending Eccles’ scientific rigor with Popper’s philosophical depth.

Karl Popper: The philosopher of the three worlds

Karl Popper, a towering figure in the philosophy of science, is best known for introducing the principle of falsifiability, the idea that a theory must be testable and refutable to qualify as scientific. While foundational, this methodological stance represents only one facet of his thought.

Popper also proposed a holistic view of reality, dividing it into three interrelated worlds:

- World 1: The physical world, encompassing all material entities, including the brain.

- World 2: The subjective world of mental states, emotions, and conscious experience.

- World 3: The world of human-created products, such as scientific theories, works of art, and cultural knowledge.

In The Self and Its Brain, Popper elaborates on how these three worlds interact. For instance, a scientific idea from World 3 can shape a person’s mental state in World 2, which in turn may alter neural structures in World 1. This model of interconnectivity challenges strict reductionism and offers a more nuanced understanding of complex phenomena.

Popper was a vocal critic of scientific materialism, which he viewed as inadequate for explaining creativity, consciousness, and free will. Alongside Eccles, he argued that the human mind has the unique capacity to transcend the physical while remaining deeply rooted in it. One illustrative example in the book concerns free will: even a trivial decision, such as choosing a glass of water, can be seen as originating in the mind (World 2) and impacting neural activity (World 1). This encapsulates their interactionist thesis.

For Popper, consciousness resides in World 2, maintaining a degree of autonomy while continuously interacting with the brain in World 1. This framework allows for a departure from strict materialism, emphasizing that the mind cannot be wholly reduced to brain matter.

John Eccles: The neurophysiologist of interactionist dualism

John Eccles, who received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1963, left an indelible mark on neuroscience through his pioneering work on synaptic transmission, the process by which neurons communicate via chemical and electrical signals.

His research focused on how neurotransmitters, such as acetylcholine, influence neural activity and modulate functions like movement, perception, and memory. These discoveries helped elucidate the fundamental mechanisms of neural communication and contributed to our understanding of the brain’s complex circuitry.

For Eccles, synapses were not merely points of transmission; they were potential sites where the immaterial mind could interact with the physical brain. He believed that synaptic plasticity, the ability of synapses to strengthen or weaken with experience, might provide a mechanism through which consciousness could affect neural networks. This bold hypothesis, though controversial, highlights the innovative nature of his thinking.

Eccles rejected the notion that the brain’s electrical currents alone could give rise to subjective experiences such as pain or joy. In The Self and Its Brain, he contends that purely material processes are insufficient to account for the richness of conscious life. He emphasized the unique qualities of consciousness that elude reductive explanations and proposed that synapses may serve as gateways between the immaterial mind and the material brain.

His collaboration with Popper provided the philosophical scaffolding for this vision, framing it within the broader model of the three interdependent worlds.

A legacy beyond reductionism

While their theory has faced criticism for lacking direct empirical evidence, Popper and Eccles ignited a fertile interdisciplinary dialogue. Notably, neuroscientist Francis Crick dismissed their approach in The Astonishing Hypothesis (1994), describing interactionist dualism as “unverifiable speculation.” Crick asserted that the mind is solely a product of neural activity, rejecting any notion of an immaterial component.

Philosopher Daniel Dennett, in Consciousness Explained (1991), similarly criticized the idea of a direct mind-brain interaction, arguing that such models unnecessarily complicate the study of consciousness. He claimed that proponents of interactionism overlook recent advancements in artificial intelligence and neuroscience, which demonstrate how complex material processes can generate mental phenomena.

Despite these critiques, the work of Popper and Eccles continues to resonate across disciplines, including philosophy, neuroscience, theology, and clinical psychology. Their theory remains an invitation to integrate scientific and philosophical perspectives in the pursuit of understanding human consciousness.

Today, scholars like Bruno Gepner and Alexandre Ganoczy extend their legacy in novel contexts.

In his 2003 article, Psychism-Brain Relations, Interactionist Dualism, and the Gradient of Materiality, Bruno Gepner examines how neuropsychological conditions such as autism might be understood through the lens of brain-mind interaction. He proposes an ambitious hypothesis: a potential “fifth psychic dimension” that interfaces with neural structures. Using autism as a case study, Gepner argues that its manifestations reflect imbalances in this brain-mind dynamic, resonating with Popper and Eccles’ claim that such phenomena cannot be reduced to purely biological mechanisms.

Meanwhile, Alexandre Ganoczy, in his 2004 article Brain and Consciousness in Theological Anthropology, explores the dialogue between modern neuroscience and theology. He argues that contemporary theology must grapple with neuroscientific findings to revise its understanding of the soul-body relationship. Inspired by Popper and Eccles, Ganoczy offers a vision of consciousness that transcends purely material explanations, proposing a model that integrates both the physical and the spiritual. For him, consciousness represents a bridge between the tangible and the intangible, a theme central to The Self and Its Brain.

Still asking the big questions: what is the mind?

The Self and Its Brain does more than pose difficult questions, it offers bold and thought-provoking answers. By combining Karl Popper’s philosophical insight with John Eccles’ scientific expertise, the book presents a unique perspective on the relationship between mind and brain.

For the reader, it opens a window onto one of humanity’s most enduring inquiries: What is the human mind? Is it merely a byproduct of the brain, or is there something deeper, more elusive?

If these questions stir your curiosity, The Self and Its Brain is essential reading, one that may forever change how you see the world, and yourself.

References

Alexandre Ganoczy. (2004).“Cerveau et conscience en anthropologie théologique“. Recherches de Science Religieuse.

Bruno Gepner, (2003).“Relations psychisme-cerveau, dualisme interactionniste et gradient de matérialité ». Intellectica.

Crick, F. (1994). The Astonishing Hypothesis: The Scientific Search for the Soul. Simon & Schuster.

Daniel Dennett. (1991). “Consciousness Explained “.

Descartes, R. (1641). Méditations Métaphysiques.

Eccles, J. C. (1989). Evolution of the Brain: Creation of the Self. Routledge.

Popper, K., & Eccles, J. C. (1977). The Self and Its Brain: An Argument for Interactionism. Springer-Verlag.

Searle, J. (1992). The Rediscovery of the Mind. MIT Press.

Amine Lahhab

Television Director

Master’s Degree in Directing, École Supérieure de l’Audiovisuel (ESAV), University of Toulouse

Bachelor’s Degree in History, Hassan II University, Casablanca

DEUG in Philosophy, Hassan II University, Casablanca